What if driving, cycling, being a passenger or pedestrian, isn't a competition? What if it's a beautiful dance, whose purpose is to make it as easy as possible for the other people to arrive? To enjoy the journey for all its tiny dramas and interactions? Above all, to live it stress-free in a spirit of curiosity? Welcome to the world of Ogmios School of Zen Motoring.

Lessons from collaborating - #NeverMoreNeeded

Testing the water for collaboration

The most important sustainability challenges can only be solved by system change. And system change happens when people work together – collaborate - to change the system.

Collaboration is successful when the collaborators share some compelling aims. It’s not enough for everyone to nod along from the side-lines – they need to be rolling their sleeves up and getting stuck in to the game. How do you help potential collaborators find their shared aims?

Facilitating and convening when you're not neutral

Many organisations in the sustainability field do their best system-changing work when they are collaborating. And they find themselves in a challenging situation - playing the role of convening and facilitating, whilst also being a collaborator, with expertise and an opinion on what a good outcome would look like and how to get to it. This dual role causes problems. Here’s how to fix them.

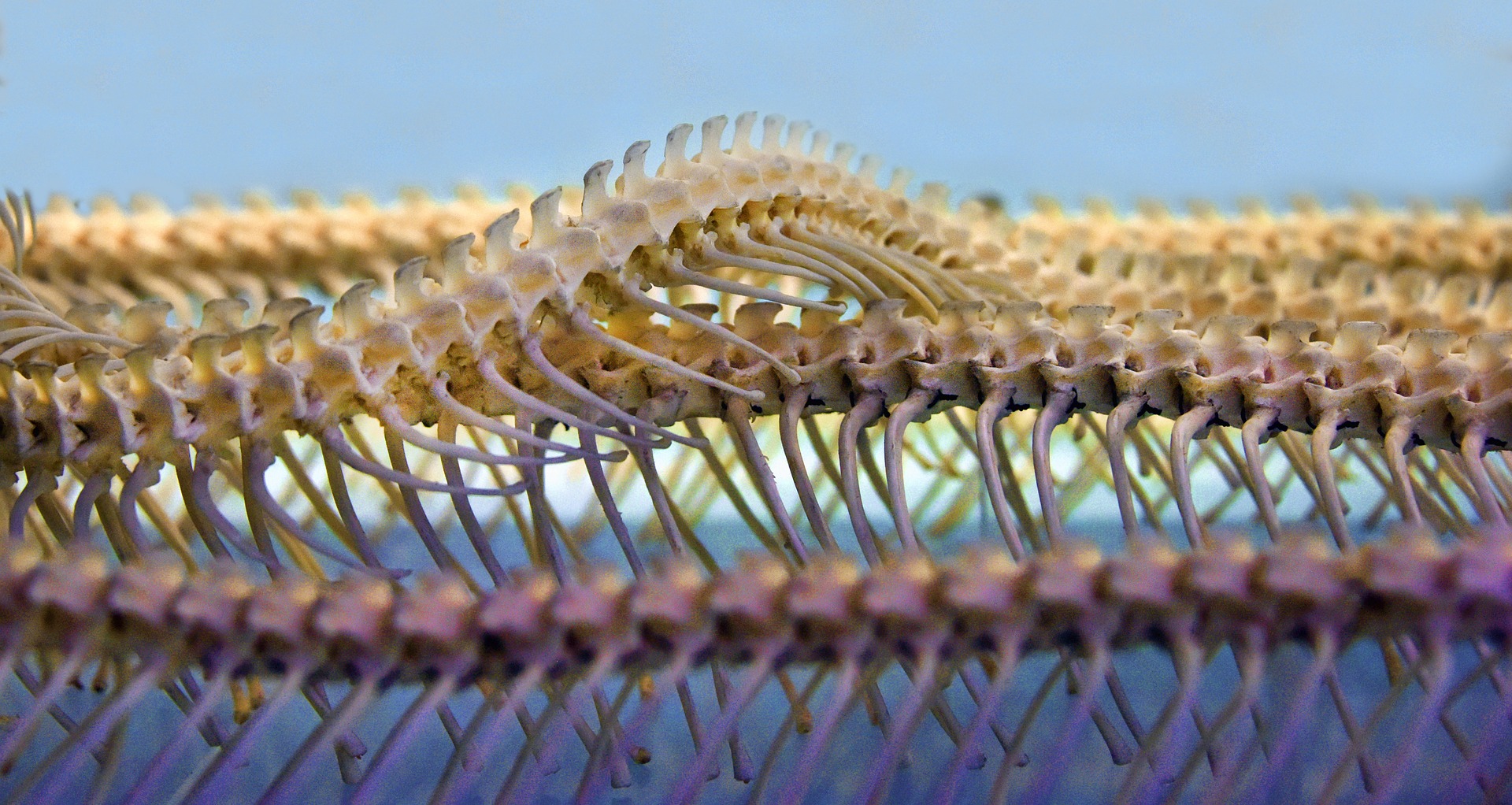

Give your collaboration some backbone!

All collaborations need a strong, flexible backbone, holding it all together, channelling communication and letting the interesting bits get on with what they’re really good at. I first came across the term ‘backbone organisation’ in the work of US organisation FSG, writing about what they call collective impact, but the need for a central team of some sort has been obvious throughout my work on collaboration. What is the ‘backbone’, and what does it do?

Who are "we"?

When people are collaborating or working in groups, there is sometimes ambiguity about where things (like policy decisions, research briefings, proposals) have come from, and who is speaking for whom. If you are convening a collaboration (or being a “backbone” organisation) this can be especially sensitive. Collaborating organisations may think that when you say “we”, you mean “we, the convenor team” when in fact you mean “we, all the collaborating organisations in this collaboration”. Or vice versa. This can lead to misunderstanding, tension, anger if people think you are either steam-rollering them or not properly including them.

Who are 'You'?

In general, think about whether to say “you” or “we”. When you use "you", there's a very clear divide between yourself and the people you are addressing. This is often going to be unhelpful in collaboration, as it can reinforce suspiscions that the collaboration is not a coalition of willing equals, but somehow a supplicant or hierarchical relationship.

Who are 'we'?

“We” is clearly more collaborative, BUT the English language is ambiguous here, so watch out!

“We” can mean

‘me and these other people, not including you’

(This is technically called ‘exclusive we’, by linguists.)

Or

‘me and you’ (and maybe some other people).

(‘Inclusive we’, to linguists.)

If you mean ‘me and you’, but the reader or listener hears ‘me and these other people, not including you’, then there can be misunderstandings.

For this reason, it can be helpful to spell out more clearly who you mean rather than just saying ‘we’.

What might this look like in practice?

These are examples from real work, anonymised.

In a draft detailed facilitation plan for a workshop, the focus question proposed was:

"What can we do to enable collaborative working?”

It was changed to:

“What can managers in our respective organisations do to enable collaborative working?”

The ‘we’ in original question was meant to signify “all of us participating in this session today” but the project group commenting on the plan interpreted it as “the organisers”. The new wording took out ‘we’ and used a more specific set of words instead.

A draft workshop report contained this paragraph:

“We do not have an already established pot of money for capital programmes that may flow from this project. One opportunity is to align existing spend more effectively to achieve the outcomes we want.”

This was changed to:

“[XXX organisation] does not have an already established pot of money for capital programmes that may flow from this project. One opportunity is to align existing spend more effectively to achieve the outcomes agreed by [YYY collaboration].”

Both uses of ‘we’ were ambiguous. The first meant ‘The convening organisation’. The second meant ‘we, the organisations and people involved in agreeing outcomes’.

The changes make this crystal clear.

Cometh the "our"

The same ambiguity applies with ‘our’. For example, when you refer to “our plan” be clear whether you mean “[Organisation XXX]’s plan” or “the plan owned by the organisations collaborating together”.

Acknowledgements

This post was originally written by Penny Walker, in a slightly different form, for a Learning Bulletin produced by InterAct Networks for the Environment Agency as part of its catchment pilot programme.

For more exciting detail on 'clusivity', including a two-by-two matrix, look here.

InterAct Networks - thank you for a wonderful ride

For over fifteen years, InterAct Networks worked to put stakeholder and public engagement at the heart of public sector decision-making, especially through focusing on capacity-building in the UK public sector. This work - through training and other ways of helping people learn, and through helping clients thinks about structures, policies and organisational change - helped organisations get better at strategically engaging with their stakeholders to understand their needs and preferences, get better informed, collaboratively design solutions and put them into practice. Much of that work has been with the Environment Agency, running the largest capacity-building programme of its kind.

History

InterAct Networks was registered as a Limited Liability Partnership in February 2002.

Founding partners Jeff Bishop, Lindsey Colbourne, Richard Harris and Lynn Wetenhall established InterAct Networks to support the development of 'local facilitator networks' of people wanting to develop facilitation skills from a range of organisations in a locality.

These geographically based networks enabled cross organisational learning and support. Networks were established across the UK, ranging from the Highlands and Islands to Surrey, Gwynedd to Gloucestershire. InterAct Networks provided the initial facilitation training to the networks, and supported them in establishing ongoing learning platforms. We also helped to network the networks, sharing resources and insights across the UK. Although some networks (e.g. Gwynedd) continue today, others found the lack of a 'lead' organisation meant that the network eventually lost direction.

In 2006, following a review of the effectiveness of the geographical networks, InterAct Networks began working with clients to build their organisational capacity to engage with stakeholders (including communities and the public) in decision making. This work included designing and delivering training (and other learning interventions), as well as setting up and supporting internal networks of engagement mentors and facilitators. We have since worked with the Countryside Council for Wales, the UK Sustainable Development Commission, Defra, DECC (via Sciencewise-ERC see p10), Natural England and primarily the Environment Agency in England and Wales.

Through our work with these organisations InterAct Networks led the field in:

diagnostics

guidance

tools and materials

new forms of organisational learning.

After Richard and Jeff left, Penny Walker joined Lindsey and Lynn as a partner in 2011, and InterAct Networks became limited company in 2012. In 2014, Lynn Wetenhall retired as a Director.

Some insights into building organisational capacity

Through our work with clients, especially the Environment Agency, we have learnt a lot about what works if you want to build an organisation's capacity to engage stakeholders and to collaborate. There is, of course, much more than can be summarised here. Here are just five key insights:

- Tailor the intervention to the part of the organisation you are working with.

- For strategic, conceptual 'content', classroom training can rarely do more than raise awareness.

- Use trainers who are practitioners.

- Begin with the change you want to see.

- Learning interventions are only a small part of building capacity.

Tailor the intervention

An organisation which wants to improve its engagement with stakeholders and the public in the development and delivery of public policy needs capacity at organisational, team and individual levels.

This diagram, originated by Jeff Bishop, shows a cross-organisational framework, helping you to understand the levels and their roles (vision and direction; process management; delivery). If capacity building remains in the process management and delivery zones, stakeholder and public engagement will be limited to pockets of good practice.

Classroom training will raise awareness of tools

There are half a dozen brilliant tools, frameworks and concepts which are enormously helpful in planning and delivering stakeholder and public engagement. Classroom training (and online self-guided learning) can do the job of raising awareness of these. But translating knowledge into lived practice - which is the goal - needs ongoing on-the-job interventions like mentoring, team learning or action learning sets. Modelling by someone who knows how to use the tools, support in using them - however inexpertly at first - and reinforcement of their usefulness. Reflection on how they were used and the impact they had.

Use trainers who are practitioners

People who are experienced and skillful in planning and delivering stakeholder and public engagement, and who are also experienced and skillful in designing and delivering learning interventions, make absolutely the best capacity-builders. They have credibility and a wealth of examples, they understand why the frameworks or skills which are being taught are so powerful. They understand from practice how they can be flexed and when it's a bad idea to move away from the ideal. We were enormously privileged to have a great team of practitioner-trainers to work with as part of the wider InterAct Networks family.

Begin with the change you want to see

The way to identify the "learning intervention" needed, is to begin by asking "what does the organisation need to do differently, or more of, to achieve its goals?", focusing on whatever the key challenge is that the capacity building needs to address. Once that is clear (and it may take a 'commissioning group' or quite a lot of participative research to answer that question), ask "what do (which) people need to do differently, or more of?". Having identified a target group of people, and the improvements they need to make, ask "what do these people need to learn (knowledge, skills) in order to make those improvements?". At this stage, it's also useful to ask what else they need to help them make the improvements (permission, budget, resources, changes to policies etc). Finally, ask "what are the most effective learning interventions to build that knowledge and those skills for these people?". Classroom training is only one solution, and often not the best one.

Learning interventions are (only) part of the story

Sometimes the capacity that needs building is skills and knowledge - things you can learn. So learning interventions (training, coaching, mentoring etc) are appropriate responses. Sometimes the capacity "gap" is about incentives, policies, processes or less tangible cultural things. In which case other interventions will be needed. The change journey needs exquisite awareness of what 'good' looks like, what people are doing and the impact it's having, what the progress and stuckness is. Being able to share observations and insights as a team (made up of both clients and consultants) is invaluable.

The most useful concepts and frameworks

Over the years, some concepts and frameworks emerged as the most useful in helping people to see stakeholder engagement, collaboration and participation in a new light and turn that enlightenment into a practical approach.

I've blogged about some of these elsewhere on this site: follow the links.

- What's up for grabs? What's fixed, open or negotiable.

- Asking questions in order to uncover latent consensus - the PIN concept.

- How much engagement? Depending on the context for your decision, project or programme, different intensities of engagement are appropriate. This tool helps you decide.

- Is collaboration appropriate for this desired outcome? This matrix takes the 'outcome' that you want to achieve as a starting point, and helps you see whether collaborating with others will help you achieve it.

- Engagement aims: transmit, receive and collaborate. Sometimes known as the Public Engagement Triangle, this way of understanding "engagement aims" was developed originally by Lindsey Colbourne as part of her work with the Sciencewise-ERC, for the Science for All Follow Up Group.

- Who shall we engage and how intensely? (stakeholder identification and mapping)

Three-day facilitation training

As part of this wider suite of strategic and skills-based capacity building, InterAct Networks ran dozens of three-day facilitation skills training courses and helped the Environment Agency to set up an internal facilitator network so that quasi-third parties can facilitate meetings as part of public and stakeholder engagement. The facilitator network often works with external independent facilitators, contracted by the Environment Agency for bigger, more complex or higher-conflict work. This facilitation course is now under the stewardship of 3KQ.

More reports and resources

Here are some other reports and resources developed by the InterAct Networks team, sometimes while wearing other hats.

Evaluation of the use of Working with Others - Building Trust for the Shaldon Flood Risk Project, Straw E. and Colbourne, L., March 2009.

Departmental Dialogue Index - developed by Lindsey Colbourne for Sciencewise.

Doing an organisational stocktake.

Organisational Learning and Change for Public Engagement, Colbourne, L., 2010, for NCCPE and The Science for All group, as part of The Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS)’ Science and Society programme.

Mainstreaming collaboration with communities and stakeholders for FCERM, Colbourne, L., 2009 for Defra and the Environment Agency.

Thank you for a wonderful ride

In 2015, Lindsey and Penny decided to close the company, in order to pursue other interests. Lindsey's amazing art work can be seen here. Penny continues to help clients get better at stakeholder engagement, including through being an Associate of 3KQ, which has taken ownership of the core facilitation training course that InterAct Networks developed and has honed over the years. The Environment Agency continues to espouse its "Working with Others" approach, with great guidance and passion from Dr. Cath Brooks and others. Colleagues and collaborators in the work with the Environment Agency included Involve and Collingwood Environmental Planning, as well as Helena Poldervaart who led on a range of Effective Conversations courses. We hope that we have left a legacy of hundreds of people who understand and are committed to asking great questions and listening really well to the communities and interests they serve, for the good of us all.

There are phases, in collaboration

One of the useful analytical tools which we've been using in training recently, is the idea of there being phases in collaborative working. This diagram looks particularly at the long, slow, messy early stages where progress can be faltering.

Learning sets, debriefing groups: learning from doing

I've been helping organisations learn how to collaborate better. One of my clients was interested in boosting their organisation's ability to keep learning from the real-life experiences of the people who I'd trained.

We talked about setting up groups where people could talk about their experiences - good and bad - and reflect together to draw out the learning. This got me thinking about practical and pragmatic ways to describe and run learning sets.

Action learning sets

An action learning set is – in its purest form – a group of people who come together regularly (say once a month) for a chunk of time (perhaps a full day, depending on group size) to learn from each other’s experiences. Characteristics of an action learning set include:

- People have some kind of work-related challenge in common (e.g. they are all health care workers, or all environmental managers, or they all help catalyse collaboration) but are not necessarily all working for the same organisation or doing the same job.

- The conversations in the 'set' meetings are structured in a disciplined way: each person gets a share of time (e.g. an hour) to explain a particular challenge or experience, and when they have done so the others ask them questions about it which are intended to illuminate the situation. If the person wants, they can also ask for advice or information which might help them, but advice and information shouldn’t be given unless requested. Then the next person gets to share their challenge (which may be completely different) and this continues until everyone has had a turn or until the time has been used up (the group can decide for itself how it wants to allocate time).

- Sometimes, the set will then discuss the common themes or patterns in the challenges, identifying things that they want to pay particular attention to or experiment with in their work. These can then be talked about as part of the sharing and questioning in the next meeting of the set.

- So the learning comes not from an expert bringing new information or insight, but from the members of the set sharing their experiences and reflecting together. The ‘action’ bit comes from the commitment to actively experiment with different ways of doing their day job between meetings of the set.

- Classically, an action learning set will have a facilitator whose job is to help people get to grips with the method and then to help the group stick to the method.

If you want to learn a little bit more about action learning sets, there's a great briefing here, from BOND who do a great job building capacity in UK-based development NGOs.

A debriefing group

A different approach which has some of the same benefits might be a ‘debriefing group’. This is not a recognised ‘thing’ in the same way that an action learning set it. I’ve made the term up! This particular client organisation is global, so getting people together face to face is a big deal. Even finding a suitable time for a telecon that works for all time zones is a challenge. So I came up with this idea:

- A regular slot, say monthly, for a telecon or other virtual meeting.

- The meeting would last for an hour, give or take.

- The times would vary so that over the course of a year, everyone around the world has access to some timeslots which are convenient for them.

- One person volunteers to be in the spotlight for each meeting. They may have completed a successful piece of work, or indeed they may be stuck at the start or part-way through.

- They tell their story, good and bad, and draw out what they think the unresolved dilemmas or key learning points are.

- The rest of the group then get to ask questions – both for their own curiosity / clarification, and to help illuminate the situation. The volunteer responds.

- As with the action learning set, if the volunteer requests it, the group can also offer information and suggestions.

- People could choose to make notes of the key points for wider sharing afterwards, but this needs to be done in a careful way so as to not affect the essentially trusting and open space for the free discussion and learning to emerge.

- Likewise, people need to know that they won’t be judged or evaluated from these meetings – they are safe spaces where they can explore freely and share failures as well as a successes.

- Someone would need to organise each meeting (fix the time, invite people, send round reminders and joining instructions, identify the volunteer and help them understand the purpose / brief, and manage the conversation). This could be one person or a small team, and once people understand the process it could be a different person or team each time.

For peer learning, not for making decisions

Neither approach is a ‘decision making’ forum, and neither approach is about developing case studies: they are focused on the immediate learning of the people who are in the conversation, and the insight and learning comes from what the people in the group already know (even if they don’t realise that they know it). In that sense they are 100% tailored to the learners’ needs and they are also incredibly flexible and responsive to the challenges and circumstances that unfold over time.

Collaboration requires high-quality internal working : fourth characteristic

Sometimes we're drawn to the idea of collaborating because we are finding our colleagues impossible! If this is your secret motivation, I have bad news: successful collaboration requires high-quality internal working in each of the collaborating organisations.

So you need to find a way of working with those impossible colleagues too.

Why?

Third characteristic: it depends on great relationships

Second characteristic: decisions are shared

Characteristics of collaborative working, episode one of six

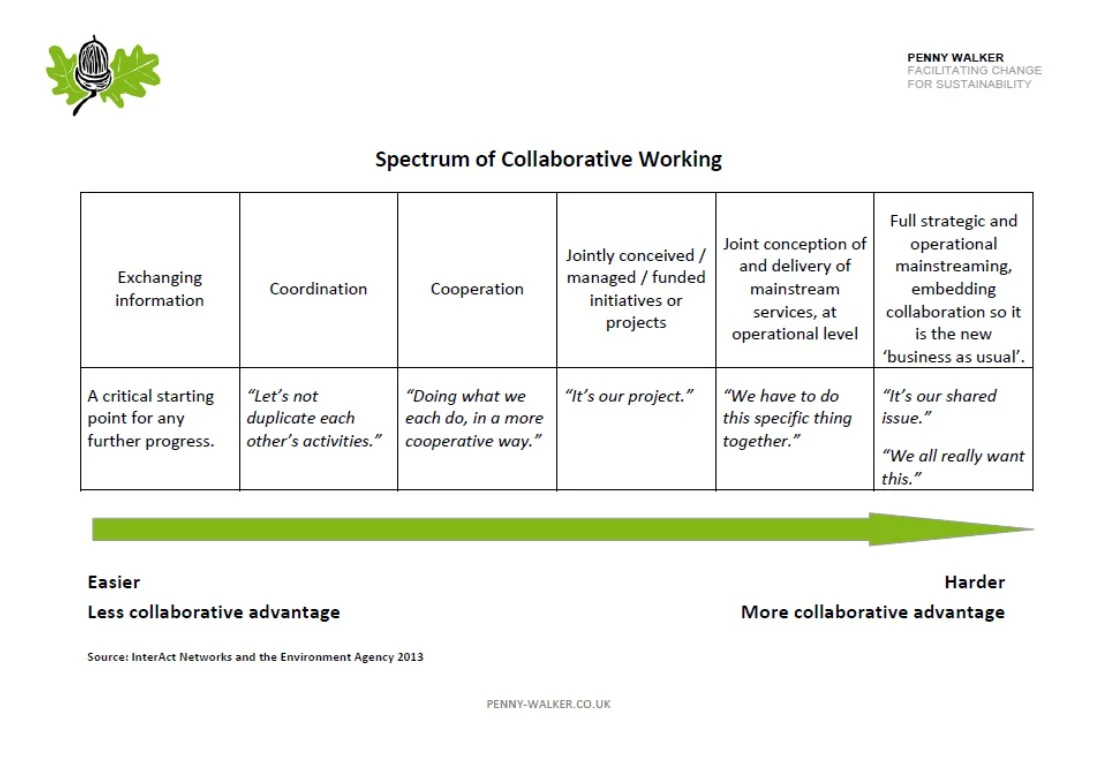

It's not all or nothing - there's a spectrum of collaborative working

Does collaboration sound like too much hard work? The examples of collaboration which get most attention are the big, the bold, the game changing.

Which can be a bit off-putting. If I collaborate, will I be expected to do something as hard and all-consuming?

Actually, most collaborative work is much more modest. And even the big and bold began as something doable.

So what kind of work might collaborators do together?

Collaborative Advantage

Collaborative Advantage needs to exist, in order for the extra work that collaborating takes to be worth it! My colleague Lynn Wetenhall puts it like this, in training and capacity building we've developed for the Environment Agency:

"Collaborative advantage is the outcomes or additional benefits that we can achieve only by working with others."

Know when to collaborate...

When contemplating collaborating, you need to make at least an initial cost-benefit judgement and this relies on understanding the potential collaborative advantage. Chris Huxham in Creating Collaborative Advantage waxes rather lyrical:

“Collaborative advantage will be achieved when something unusually creative is produced – perhaps an objective is met – that no organization could have produced on its own and when each organization, through the collaboration, is able to achieve its own objectives better than it could alone.”

But it’s even better than that!

Huxham goes on:

“In some cases, it should also be possible to achieve some higher-level … objectives for society as a whole rather than just for the participating organizations.”

So collaborative advantage is that truly sweet spot, when not only do you meet goals of your own that you wouldn’t be able to otherwise, you can also make things better for people and the planet. Definitely sustainable development territory.

...and when not to

There’s another side to the collaborative advantage coin.

If the potential collaborative advantage is not high enough, or you can achieve your goals just as well working alone, then it may be that collaboration is not the best approach.

DareMini

So DareConfMini was a bit amazing. What a day. Highlights:

- Follow your jealousy from Elizabeth McGuane

- Situational leadership for ordinary managers from Meri Williams

- The challenge of applying the great advice you give to clients, to your own work and practice from Rob Hinchcliffe

- Finding something to like about the people who wind you up the most from Chris Atherton

- Being brave enough to reveal your weaknesses from Tim Chilvers

- Jungian archetypes to help you make and stick to commitments from Gabriel Smy

- Radical challenges to management orthodoxy from Lee Bryant

- Meeting such interesting people at the after party

No doubt things will continue to churn and emerge for me as it all settles down, and I'll blog accordingly.

In the meantime, all the videos and slides can be watched here and there are some great graphic summaries here (from Francis Rowland) and here (from Elisabeth Irgens)

There are also longer posts than mine from Charlie Peverett at Neo Be Brave! Lessons from Dare and Banish the January blues – be brave and get talking from Emma Allen.

If you are inspired to go to DareConf in September, early bird with substantial discounts are available until 17th February.

Many thanks to the amazing Jonathan Kahn and Rhiannon Walton who are amazing event organisers - and it's not even their day job. They looked after speakers very well and I got to realise a childhood fantasy of dancing at Sadler's Wells. David Caines drew the pictures.

Deadlines

Do deadlines help a group reach consensus? Or do they get in the way? Yesterday brought the news that the latest round of talks in the peace process in Northern Ireland had broke up without agreement, the deadline having passed. There's a report from the BBC here.

I make no comment on the content of the talks, but I am interested in the process. Why was this particular deadline set? And do deadlines help by providing a sense of jeopardy - a time when the Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement comes into play? Or by restricting the time for exploration and low-anxiety creativity, do they get in the way of positive consensus?

Deadlines for discussion and agreement may be tied to objective events in the real world: mother and midwife need to agree how to manage labour before it happens. They may be tied to objective but less predictable events: the Environment Agency and the stakeholders discussing details of the Medmerry Managed realignment flood defence scheme wanted to get it built in time to protect the area from the higher risk of winter storms and flooding. Or they may be tied to other events which are choices rather than unstoppable events, but ones where choosing not to meet the deadline would have very large consequences: the Environment Agency and the Olympic Delivery Authority needed to agree how to handle drainage and water quality from the Stratford Olympic site in time for the games to happen in 2012.

I may be missing something, but the Haass talks don't seem to have any of these justifiable external pressures. So why the deadline?

A moment of commitment - reflections on writing

Tempting and disconcerting in equal measure: being asked to write a book is such a flattering thing, dangerously seductive; being asked to write a book is such a frightening thing, because "what if it's rubbish?" Putting something in writing is a moment of commitment: hard for an inveterate hedger and fence-sitter like me. (I couldn't even decide between 'hedger' and 'fence-sitter', could I?)

Avoiding temptation, taking courage

In an attempt to stop it being rubbish, and to remind myself that it's not me that's being flattered - it's the wise things I've learnt from others - I made a conscious choice to stand on shoulders of giants both for theory and for tips that really make a difference, when writing Working Collaboratively.

I found some great academic research and theory before I decided that I really needed to stop reading and get on with writing. But it was more on 'collaborative governance' (advising others on how to do things) than multi-sector collaboration to get things done. Noticing that distinction helped me decide what to get my teeth into.

What kind of collaboration?

I knew I wanted to include examples, and there were plenty out there even from a cursory look. But I wanted to find ones which were more than contractual, more than cause-related marketing, and which involved multiple collaborators not just two (you can't change a system with just two players). I wasn't so interested in crowd-sourcing, where the hive mind is used to generate multiple clever ideas which might be the solution, but stops short of putting collaborative solutions into practice. That feels like another form of consultation to me.

It's not to say these are bad things: but to me they are less difficult and less necessary than when collaboration is a way to solve system-level wicked problems, where there is a need for simultaneous action by players who each bring a different piece of the jigsaw with them.

So I drew up some criteria and then searched for examples which both met those criteria and that I had a head-start with: knowing key players, for example, who I could be confident would at least read my email or return my call.

Hearty thanks to everyone who made time to be interviewed or to give me their perspective on some of the examples.

Book writing as a project

The project has followed a pattern I'm now pretty familiar with, in my consulting, training and facilitation work:

- excitement and disbelief at being invited to do such a cool thing;

- fear that I'll have nothing interesting or useful enough to say;

- writing myself a little aide memoire to keep those pesky internal voices at bay;

- mind mapping key points and allocating word count (in a training or facilitation situation, that would allocating minutes!);

- less familiar was the long research phase, which is not something have to do very often and was a real luxury;

- identifying examples and interviewees.

Then the actual creativity begins: knitting new things, finding scraps of existing articles, handouts or blogs to recycle and stitching it together like a quilt with additional embroidery and applique. I start committing myself to a narrative thread, to a point of view, to some definitive statements.

Then the first of many moments of truth: sending the draft off and nervously awaiting the feedback - sitting over my email until it arrives and then putting off the moment of actually opening it and reading the response.

Altering and amending the draft in response to that feedback and to my own nagging unhappiness with how I've captured something which may be very hard to pin down.

And then there's a dip: the boredom as I get too familiar with the material: is there anything new here? Will anyone else find it interesting?

At that point I know I need to leave it all to settle for a bit and come back to it fresh after some weeks. Fortunately, when I did, I felt "yes, this is what I wanted to say, this is how I wanted to say it" and crucially: "this has got things in it that readers will find useful, amusing, novel, easy to understand."

Collaboration of goodwill

It's sobering and enlightening to remember how much goodwill was involved - interviewees, people who gave me permission to use models and frameworks; anonymous and other reviewers; people helping to get the word out about it. There was a lot of swapping favours and continuing to build and reinforce working relationships. It might be possible to analyse these all down to hard-nosed motivations, but I think much of it was trust-based and fuelled by enthusiasm for the topic and a long history of comfortable working relationships.

What did I say?

As an author, it feels as if the project is ended when the final proofs go back to the publisher. But of course it doesn't, thankfully, end there. Now that I've been invited to blog, present or share expertise off the back of the book (e.g. Green Mondays, MAFN, DareConf) I have to remind myself of what I've written! Because your thinking doesn't stand still, nor should it.

What you need from your facilitator, when you're collaborating

Researching Working Collaboratively, I heard a lot about the importance of a skillful facilitator. And you can see why. Collaboration happens when different people or organisations want to achieve something - and they need common ground about what it is they want to achieve. They might both want the same thing or they may want complementary things. Since finding common ground is not easy, it's good to know facilitators can help.

Common ground, common process

But it's not just common ground on the goals that need to be achieved, it's common ground on the process too. It's essential to be able to find ways to work together (not just things to work together on).

Process can be invisible - you're so used to the way your own organisation does things, that you may not see that these processes are choices. And it's possible to choose to do things in other ways.

This can be as simple as using descriptive agendas (which set out clearly what the task is for each item e.g. 'create a range of options', 'discuss and better understand the options', 'identify the group's top three options', 'agree which option to recommend', 'agree which option to take forward') rather than the more usual summary version (Item 1: options).

Or it might be agreeing to set up special simultaneous consultation and decision mechanisms within each of the collaborating organisations rather than each one going at its own usual, different, pace.

To be able to make these choices, process needs to be brought to conscious awareness and explicitly discussed. This will be a key part of any facilitator's role.

Disagreement without conflict

Collaboration is about agreement, of course. But if the organisations have identical aims and ways of meeting them, then they might as well merge rather than collaborate! In collaboration, you must also expect disagreement and difference.

Sometimes people may be so keen to find the common ground, that discussing the areas of disagreement and difference becomes taboo. Much more healthy is being able to discuss and acknowledge difference in an open and confident way. A facilitator who is used to saying: "I notice that there is a difference of view here. Let's understand it better!" in a perky and comfortable way can help collaborators be at ease with disagreement.

Building trust

Your facilitator will also need to help you be open about the constraints and pressures which are limiting your ability to broaden the common ground about desired outcomes or process. Perhaps a public body cannot commit funds more than one year ahead. Perhaps a community or campaign group needs to maintain its ability to be publicly critical of organisations it is collaborating with. A business may need to be able to show a return on investment to shareholders. In most cases, the people 'in the room' will need to take some provisional decisions back to their organisation for ratification.

Just like the areas of disagreement, these constraints can be hard to talk about. Some clients I work with express embarrassment bordering almost on shame when they explain to potential collaborators the internal paperwork they 'must' use on certain types of collaborative project.

Much better to be open about these constraints so that everyone understands them. That's when creative solutions or happy compromises arise.

A neutral facilitator?

Do you need your facilitator to be independent, or do they need to have a stake in the success of the collaboration? This is the 'honest broker / organic leader' conundrum explored here.

I have seen real confusion of process expertise and commitment to the content, when collaborative groupings have been looking for facilitation help. For example, the UK's Defra policy framework on the catchment based approach to improving water quality seems to assume that organisations will offer to 'host' collaborations with minimal additional resources. If you don't have a compelling outcome that you want to achieve around water, why would you put yourself forward to do this work? And if you do, you will find it hard (though not impossible) to play agenda-neutral process facilitator role. There is a resource providing process advice to these hosts (Guide to Collaborative Catchment Management), but I am not sure that any of them have access to professional facilitation.

This is despite the findings of the evaluation, which say that facilitation expertise is a 'crucial competency':

"Going forward, pilot hosts indicate that funding, or in-kind contribution, for the catchment co-ordinator and independent facilitation roles is essential." (p8)

And Defra's own policy framework makes clear that involving facilitators is crucial to success:

"Utilising expert facilitation to help Partnerships address a range of issues for collaborative working including stakeholder identification and analysis, planning meetings, decision-making and engaging with members of the public [is a key way of working]."

There seems to be some understanding of the agenda-neutral facilitation role, but a lack of real answers to how it will be resourced.

I will be fascinated to see how this plays out in practice - do comment if you have experience of this in action.

How can I get them to trust me?

Trust is essential to collaborative work and makes all kinds of stakeholder engagement more fruitful. Clients often have 'increased trust' as an engagement objective. But how do you get someone to trust you?

Should they?

My first response is to challenge back: should people trust you? Are you entering this collaboration or engagement process in good faith? Do you have some motives or aims which are hidden or being spun? Do some people in your team see consultation and participation as just more sophisticated ways of persuading people to agree with what you've already made up your mind about? Or are you genuinely open to changing things as a result of hearing others' views? Is the team clear about what's up for grabs?

It's an ethical no-brainer: don't ask people to trust you if they shouldn't!

Earn trust

Assuming you do, hand on heart, deserve trust, then the best way to get people to trust you is to be trustworthy.

Do what you say you're going to do. Don't commit to things that you can't deliver.

Don't bad-mouth others - hearing you talk about someone one way in public and another in a more private setting will make people wonder what you say about them when they're not around.

Trust them

The other side of the coin is to be trusting. Show your vulnerability. Share information instead of keeping it close. Be open about your needs and constraints, the pressures on you and the things that you find hard. If you need to give bad news, do so clearly and with empathy.

Give it time

Long-term relationships require investment of time and effort. Building trust (or losing it) happens over time, as people see how you react and behave in different situations.

Be worthy of people's trust, and trust them.