There are some venues which make my heart soar – and some which make it sink! What can you find out about a venue ahead of time, which will help you pick a great place and enable you to design your event or workshop to suit its idiosyncrasies? Here’s a great five-point checklist.

Instant bar charts: a safe snapshot of opinion

Carousel in action

Campaigners, community groups, activists and faith groups - run your business meetings better so you can get on with the important stuff!

If you're involved in a local group - campaigners, activists, community action, faith group - there will be some really important things you want to achieve in the world. And you'll have some kind of team, committee, council or similar organising the activities behind the scenes. How are those meetings? Clear, engaging, effective? Or dull, interminable, frustrating, repetitive?

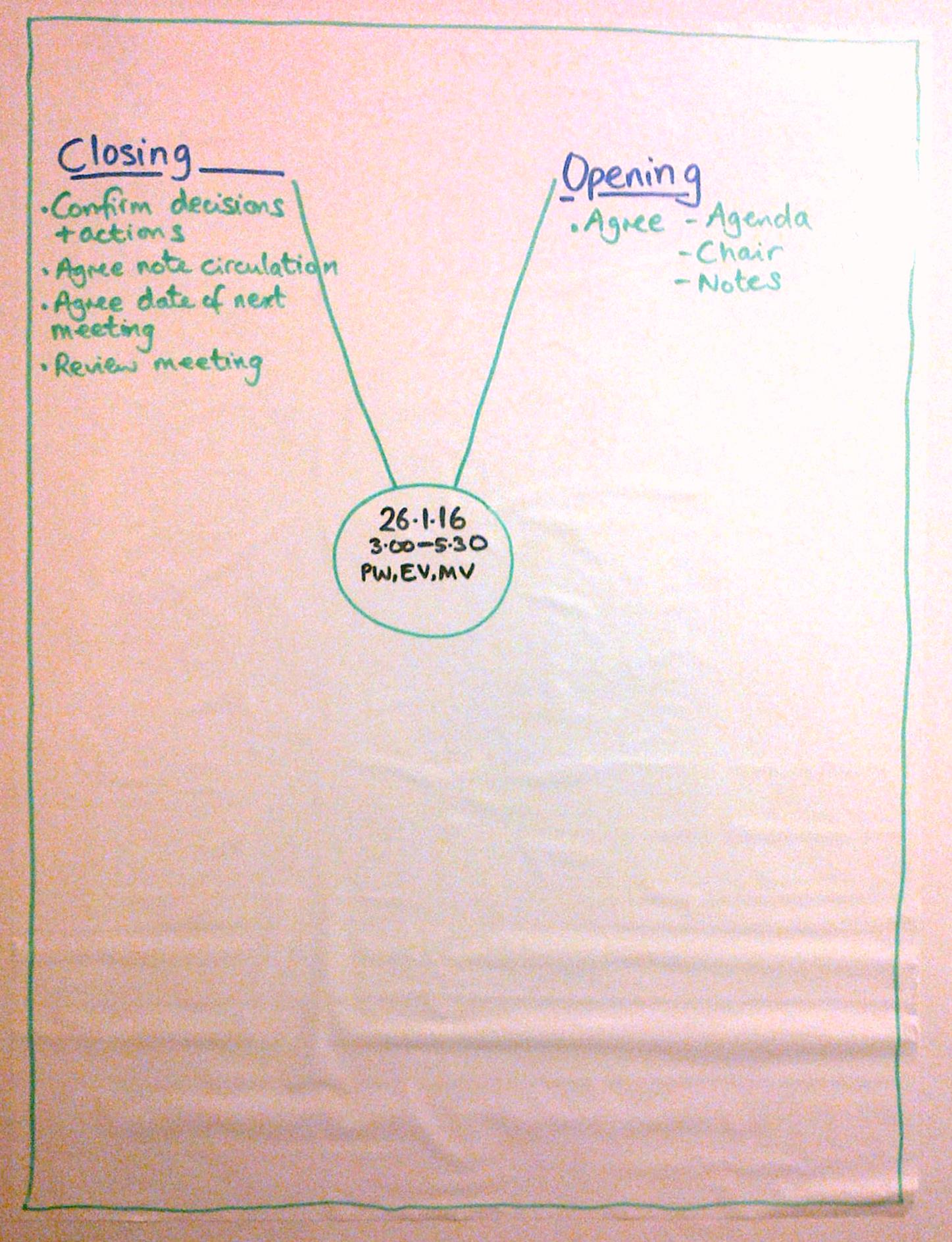

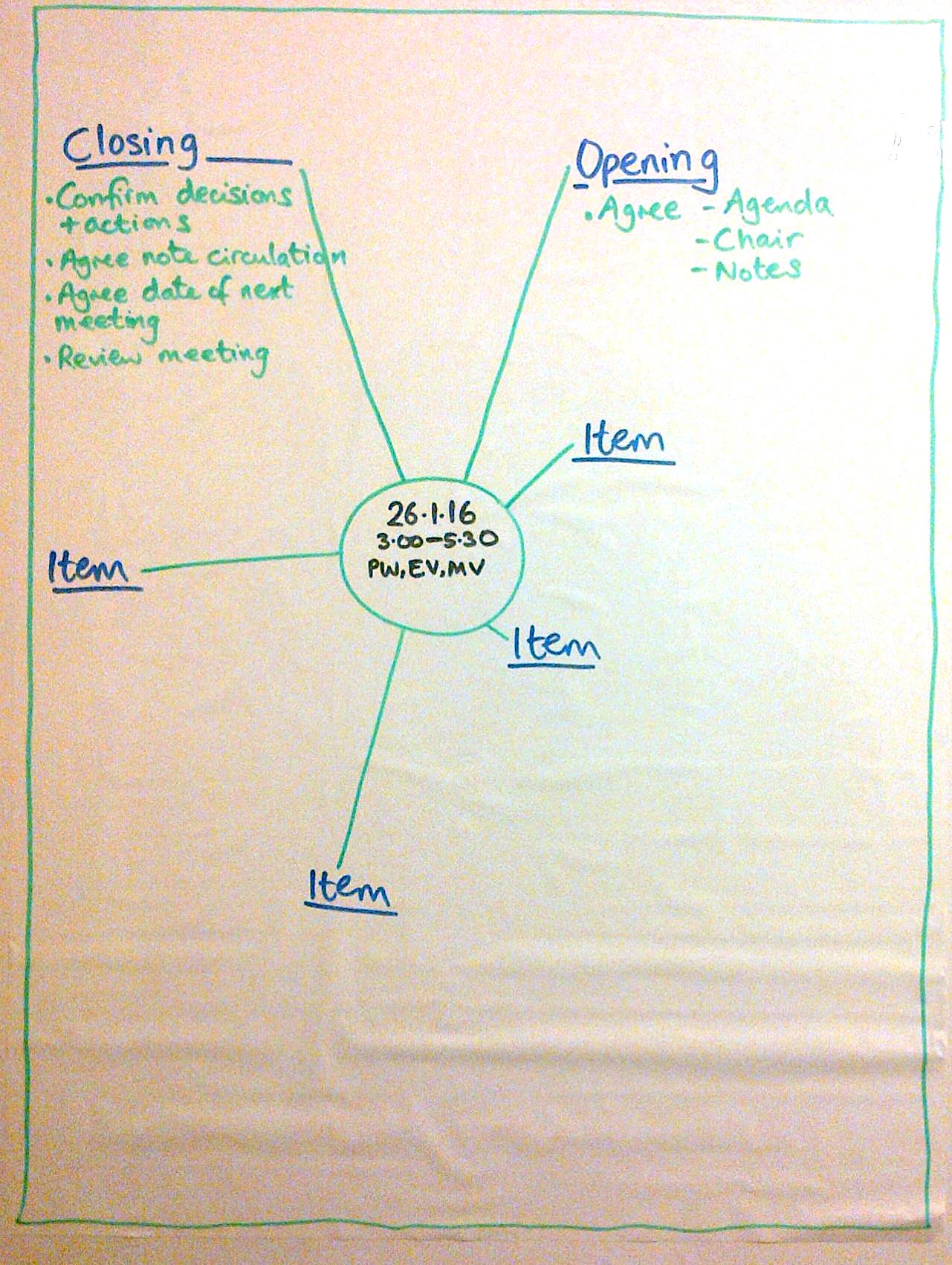

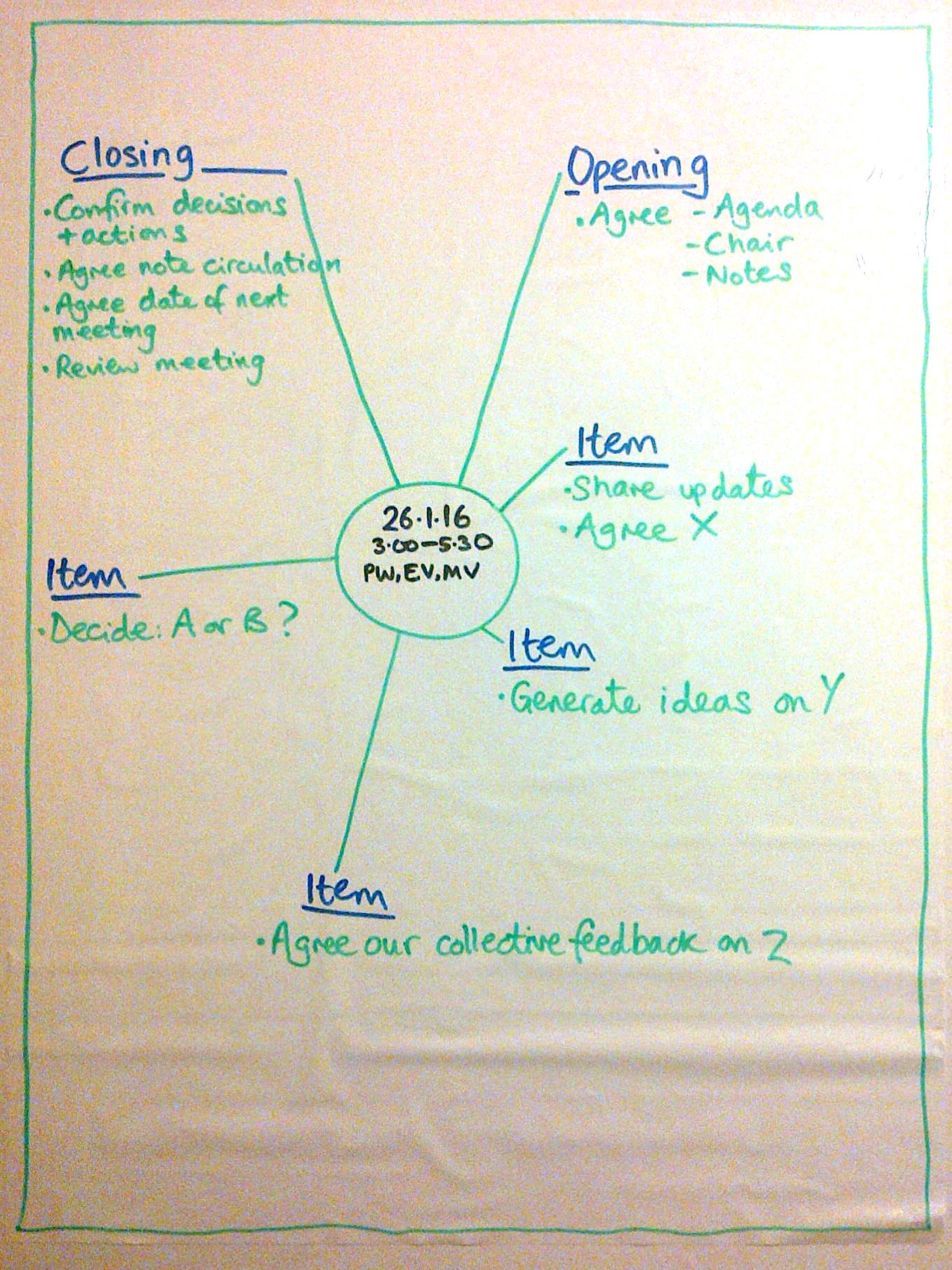

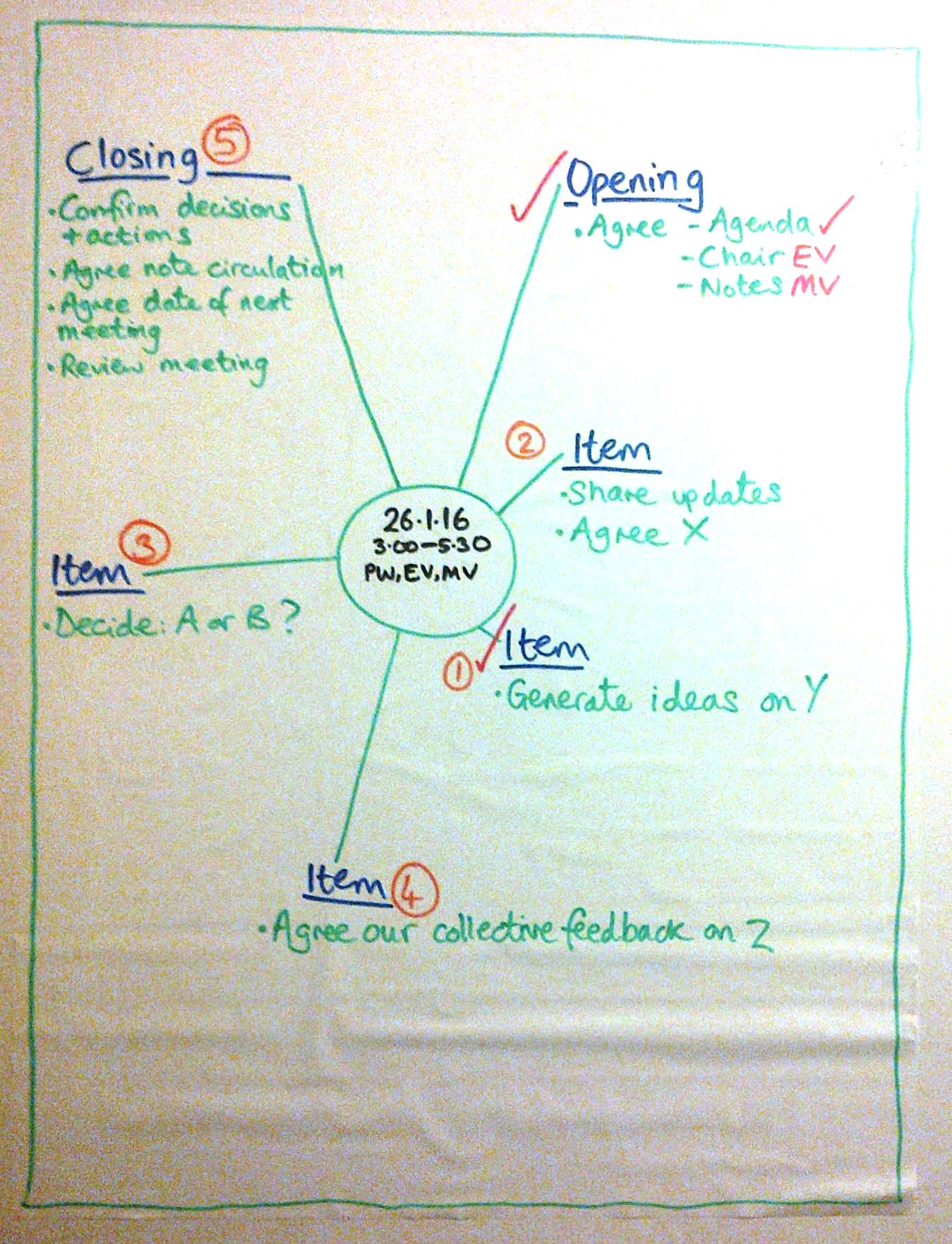

I've led a couple of two-hour training sessions this year for groups on how to run meetings which make clear decisions that stick. So that they can spend time on doing the stuff that really matters.

Here are the handouts from the workshop I ran in mid November.

If you think your group would benefit, get in touch to see what I can do to help you.

5 minute meeting makeover

We know it shouldn’t be like this, but sometimes we find ourselves in a meeting which is ill-defined, purposeless and chaotic.

Maybe it’s been called at short notice. Maybe everyone thought someone else was doing the thinking about the agenda and aims. Maybe the organisation has a culture of always being "too busy" to pay attention to planning meetings.

For whatever reason, you’re sitting there and the conversation has somehow begun without a structured beginning.

This is the moment to use the five minute meeting makeover!

Decisions? Decisions!

This blog post pulls together some resources that I shared at a workshop last week, for people in community organisations wanting to make clear decisions that stick. Groups of volunteers can't be 'managed' in the same that a team in an organisation is managed: consensus and willingness to agree in order to move forward are more precious. Sometimes, however, that means that decisions aren't clear or don't 'stick' - people come away with different understandings of the decision, or don't think a 'real' decision has been made (just a recommendation, or a nice conversation without a conclusion). And so it's hard to move things forward.

I flagged up a number of resources that I think groups like this will find useful:

- Descriptive agendas - that give people a much clearer idea of what to expect from a meeting;

- Using decision / action grids to record the outputs from a meeting unambiguously;

- Be clear about the decision-making method (e.g. will it be by consensus, by some voting and majority margin, or one person making the decision following consultation?) and criteria.

- Understanding who needs to be involved in the run-up to a decision.

- Taking time to explore options and their pros and cons before asking people to plump for a 'position'.

The morning after the night before - debriefing events

A lot of projects have been completed in the last couple of weeks, so I've been encouraging clients to have debriefing conversations.

Although I always include some kind of debrief in my costings, not all clients find the time to take up this opportunity. That's such a shame! We can learn something about how to bring people together to have better conversations, every time we do it.

Structuring the debrief

I've been using a simple three question structure:

- What went well?

- What went less well?

- What would you do differently, or more of, next time?

This works in face to face debriefing, telecons and can even form a useful way of prompting a debriefing conversation that takes place in writing: in some kind of joint cyberplace, or by email.

If we haven't already had a conversation about immediate next steps, then I'll add this fourth question:

- What do we need to do next?

Referring back to the aims

Since, for me, the aims are the starting point for the design process, they should also be the starting point for the debriefing conversation. To what extent did we meet our aims? What else might the client team need to do in next weeks and months, to get closer to meeting the aims?

Evidence to draw on

It's really helpful for the team to have access to whatever the participants have fed back about how the process or event worked for them. Sometimes we use paper feedback forms in the room, sometimes an electronic survey after the event. Quantitative and qualitative reports based on this feedback can help people compare their intuitive judgements against what participants have said.

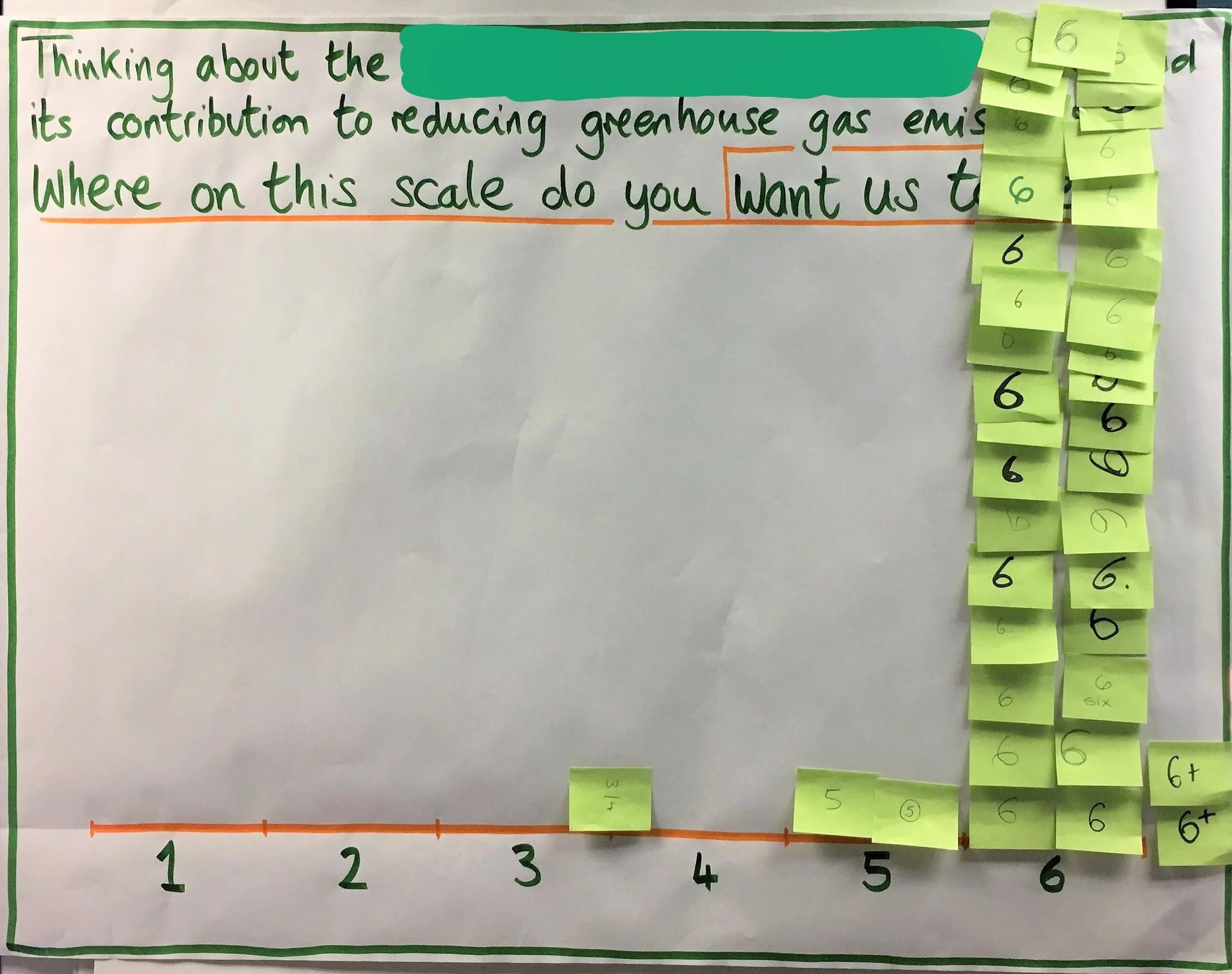

In other situations, we make time in the process for participants to have their own conversation about how things have gone. A favourite technique is to post up a flip with an evaluation question like "to what extent did we meet our aims?". The scale is drawn on, and labelled "not at all" to "completely". Participants use dots to show their response to the question, and then we discuss the result. I often also post up flips headed "what helped?" and "what got in the way?". People can write their responses directly on to the flips. This is particularly useful when a group will be meeting together again, and can take more and more responsibility for reflecting on and improving its ways of working effectively.

What's been learnt?

Some of the unexpected things to have come out of recent debriefs:

- The things that actually get done may be more important than the stated aims: one workshop only partially met its explicit aims to develop consensus on topic X, but exceeded client expectations in building better working relationships, making it easier to talk later about topic Y.

- What people write in their questionnaire responses can be quite different to the things you heard from one or two louder voices on the day.

- A debriefing conversation can be a good way of briefing a new team member.

And the obvious can be reinforced too: clarity on aims really helps, thinking about preparation and giving people time to prepare really helps, allowing and enabling participation really helps, good food really helps!

Some lessons from Citizens Juries enquiring into onshore wind in Scotland

I've been reading "Involving communities in deliberation: A study of 3 citizens’ juries on onshore wind farms in Scotland" by Dr. Jennifer Roberts (University of Strathclyde) and Dr. Oliver Escobar (University of Edinburgh), published in May 2015.

This is a long, detailed report with lots of great facilitation and public participation geekery in it. I've picked out some things that stood out for me and that I'm able to contrast or build on from my own (limited) experience of facilitating a Citizens' Jury. But there are plenty more insights so do read it for yourself.

I've stuck to points about the Citizen Jury process - if you're looking for insights into onshore wind in Scotland, you won't find them in this blog post!

What are Citizens' Juries for?

This report takes as an underlying assumption that its focus - and a key purpose of deliberation - is learning and opinion change, which will then influence the policies and decisions of others. The jury is not seen as "an actual decision making process" p 19

"Then ... the organisers feed the outputs into the relevant policy and/or decision making processes." p4

In the test of a Citizens’ Jury that I helped run for NHS Citizen, there was quite a different mandate being piloted. The idea is that when the Citizens’ Jury is run ‘for real’ in NHS Citizen, it will decide the agenda items for a forthcoming Board Meeting of NHS England.

This is a critical distinction, and anyone commissioning a Citizens’ Jury needs to be very clear what the Jury is empowered to decide (if anything) and what it is being asked for its views, opinions or preferences on. In the latter case, the Citizens’ Jury becomes essentially a sophisticated form of consultation.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it needs to be very clear from the start which type of involvement is being sought.

Having confidence in the Citizens’ Jury process

To be a useful consultant mechanism, stakeholders and decision-makers need to have confidence in the Citizens’ Jury process. This applies even more strongly when the Jury has decision-making powers.

The organisers and commissioners need to consider how to ensure confidence in a range of things:

- the selection of jurors and witnesses,

- the design of the process (including the questions jurors are invited to consider and the scope of the conversations),

- the facilitation of conversations,

- the record made of conversations and in particular decisions or recommendation,

The juries under consideration in this report benefited from a Stewarding Board. This type of group is sometimes called a steering group or oversight group. It’s job is to ensure the actual and perceived independence of the process, by ensuring that it is acceptable to parties with quite difference agendas and perspectives. If they can agree that it’s fair, then it probably is. Chapter 3 of the report looks at this importance of the Stewarding Board, its composition and the challenging disagreements it needed to resolve in this process.

In our NHS Citizen test of the Citizens’ Jury concept, we didn’t have an equivalent structure, although we did seek advice and feedback from the wider NHS Citizen community (for example see this blog post and the comment thread) as well as from our witnesses, evaluators with experience of Citizens’ Juries. We also drew on our own insights and judgements as independent convenors and facilitators. My recommendation is that there be a steering group of some kind for future Citizens’ Juries within NHS Citizen.

What role for campaigners and activists?

The report contains some interesting reflections on the relationship between deliberative conversations in ‘mini publics’ and citizens who have chosen to become better informed and more active on an issue to the extent of becoming activists or campaigners. (Mini public is an umbrella term for any kind of “forum composed of citizens who have been randomly selected to reflect the range of demographic and attitudinal characteristics from the broader population – e.g. age, gender, income, opinion, etc.” pp3-4)

The report talks about a key feature of Citizens’ Juries being that they

“...use random selection to ensure diversity and thus “reduce the influence of elites, interest advocates and the ‘incensed and articulate’”

(The embedded quote is from Carolyn Hendriks’ 2011. The politics of public deliberation: citizen engagement and interest advocacy, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.)

So what is the role of the incensed and the articulate in a Citizens’ Jury? The detail of this would be decided by the steering group or equivalent, but broadly there are two roles outlined in the report: being a member of the steering group and thus helping to ensure confidence in the process; and being a witness, helping the jurors to see multiple aspects of the problem they are considering. See pp 239-240 for more on this.

Depending on the scope of the questions the Citizens’ Jury is being asked to deliberate, this could mean a very large steering group or set of witnesses. The latter would increase the length of the jury process considerably, which makes scoping the questions a pragmatic as well as a principled decision.

The project ran from April 2013 to May 2015. You can read the full report here.

Thanks very much to Clive Mitchell of Involve who tipped me off about this report.

See also my reflections on the use of webcasting for the NHS Citizen Citizens' Jury test.

What kind of workshop? Some metaphors

I've been working with a small client team to design a workshop. The client team see lots of weaknesses in the current set-up that the group is a part of. As the fighter pilot said when surrounded by enemy planes, it is a target-rich environment. So where do we begin?

We discussed jumping in and asking the biggest, baddest questions about the group's role and existence. We played around with focusing on process tasks like revisiting terms of reference. We thought about starting with easy wins.

The someone suggested a garden metaphor: the group and its work is a garden and - so he thought - the implication is that we want to do something evolutionary not revolutionary.

Maybe.

It got me thinking about the different kinds of interventions you might make in a garden - which could be radical as well as incremental - and we used these metaphors to help us reach a clearer common view about what the workshop should be like.

Dreaming of warm sunny evenings

Especially at this time of year, when nothing much is growing and the days are moist and cold, many gardeners will be dreaming of long summer evenings with a glass of wine and artfully placed candles. Scents and seating and shade. We could use the workshop to dream about the desired future, building a rich shared vision that inspires us during the hard months ahead.

Rip it up and start again

Not all interventions in gardens are evolutionary. People sometimes decide to completely remodel their garden: hard landscaping, tree removal, new soil, the works. So a workshop could work on new plans: where to put the pond, as it were. And people could even move on to project planning: when to get the diggers in.

Weeding party

Or the workshop could be like a work party: lots of practical immediate stuff to get on with: weed the borders, turn the compost heap, sew the broad beans and repair the fence.

Using metaphors helped us decide

Tossing these options around helped us decide on the kind of workshop we wanted, before we agreed on the detailed draft aims. We went for the weeding party. Trowels at the ready!

What metaphors have helped you, in designing and planning workshops?

Don't be an expert - at least, not yet

The trouble with being an expert is that you are expected to come up with solutions really fast. Or you think you are. Doubly so if you're an advocate or a campaigner. You can be tripped up by your own assumptions about your role, and stumble into taking a position much too early. And once you've taken a position, it feels hard to climb down from it and explore other options.

Which can be a big mistake.

Don't be an expert, yet

Pretty much every project you'll ever work on has more than one noble aim (or, at least, more than one legitimate aim). On time, on budget. For people, profit and planet. Truth and beauty.

Not much point designing the shiniest, coolest, sexiest thing that can't be built. Or the safest, most ethical, handcrafted whoosit that's too expensive for anyone to buy. Or running an organic, fair trade eco-retreat which can only be reached by helicopter.

If a critical variable needs to 'lose' in order that the thing you have committed yourself to can 'win', you've set it up wrong.

Why set it up as a zero-sum game, when it could be that there's a win-win solution enabling everyone to get everything they want? (I could tell you about boogli fruit, but once again I'd have to kill you.)

Not everything is a fight

If you frame it as a fight, you'll get a fight. If you frame it as a complex problem with a mutually-beneficial solution that hasn't been found yet - you may just get it.

But how can you help the conversation be a dialogue rather than a gun-fight?

You need to stay in that uncomfortable place of not knowing. Listen well. Ask questions.

Above all, maintain an attitude of respect, curiosity and trust.

Want to explore further?

I'll be talking more about this at #DareConf Mini on 20th January - still time to join me and some awesome speakers.

And here's a New Year's gift to help: £100 off if you use code PENNY when booking.

Location, location, location

Picture the scene: the room, which you haven't been able to check out before, has a low ceiling, tiny windows that somehow don't manage to let in much light, and is decorated in shades of brown and purple. There are uplighters on the walls, which have large strategically placed paintings screwed to them. And, of course, you have been told that under no circumstances can blu-tack be used on the rough-textured wallpaper.

What your facilitator will ask!

So you've decided that the meeting or workshop you have in mind needs an independent, professional facilitator. You call them up and guess what? They start asking all these awkward questions. What's that about?

Facilitators don't just turn up and facilitate

Facilitated meetings are increasingly popular, and many teams and project groups understand the benefits of having their workshop facilitated. More and more organisations are also wanting to have meaningful, productive conversations with stakeholders, perhaps even deciding things together and collaborating. Facilitated workshops can be a great way of moving this kind of thing forward. But facilitators don't just turn up and facilitate. So what are the key things a facilitator will want to know, when they're trying to understand the system, before the big day itself?

Start with the ends

Your facilitator will always begin with the purpose or objectives - why is the meeting being held? What do you want to be different, after the meeting? This could be a difference in the information that people have (content), new agreements or decisions (process), or it could be that what is needed is a shift in the way people see each other (relationships) - or some of each of these things.

Context and history

Once the facilitator is confident that you are clear about the purpose (and this could take some time - the facilitator should persist!), then the facilitator will want to understand the context, and the people.

Context includes the internal context - what has you organisation done up to now, what other processes or history have led up to this workshop? It also includes the external context - what in the outside world is going to have an impact on the people in the room and the topic they are working on?

Who's coming?

Often, the one thing that has been fixed before the facilitator gets a look in is the people who have been invited. But are they the right people to achieve the objectives? Have some important oilers or spoilers, information holders or information needers been left out? And do they understand clearly what the objectives of the meeting are?

Getting the right people in the room (and making arrangements to involve people who need to take part, but can't actually be there on the day) is just part of it. What do the people need to know, in order to play an effective part in the meeting? And how far ahead does this information need to be circulated? Apart from passively receiving information, what information, views or suggestions can be gathered from participants before the meeting, to get people thinking in advance and save time for interaction and creative discussion on the day? What questions can be gathered (and answered) in advance?

What do the participants want out of the meeting? If this is very different to what the client or sponsor wants, then this gap of expectations needs to be positively managed.

When and where?

Apart from the invitation list, the other things which are usually fixed before the facilitator is brought in, and which they may challenge, with justification, are the date and the venue.

The date needs to be far enough away to ensure that participants get adequate notice, and the facilitator, client team and participants get adequate preparation time.

The venue needs to be suitable for the event - and for a facilitated meeting, traditional conference venues may not be. Inflexible room layout, a ban on blu-tack, rigid refreshment times - all of these make a venue hard to use, however handy it may be for the golf course. There's more on venues here.

Workshop design

Sometimes, of course, the date, venue and participant list are unchangeable, whatever the facilitator would like, and have to be taken as fixed points to be designed around. So what about the overall meeting design? The facilitator will want to understand any 'inputs' to the meeting, and where they have come from. They'll want to talk about the kind of atmosphere which will be most helpful, and about any fixed points in the agenda (like a speech by the Chief Exec), and how these can be used most positively.

A design for the meeting will be produced, and circulated to key people (the client, maybe a selection of participants), and amended in light of their comments. But the facilitator will always want to retain some flexibility, to respond to what happens 'in the room'.

What next?

And after the meeting? The 'after' should be well planned too - what kind of report or record is needed, and will there be different reports for different groups of people? This will have an impact on the way the meeting is recorded as it goes along - e.g. on flip chart paper, on display for all to see and for people to correct at the time. If there are specific 'products' from the meeting (agreements, action points, priorities, principles or statements of some kind, options or proposals), what is going to happen to them next?

And how will the client, facilitator and participants give and receive feedback about how the process worked?

All these things will need to be thought about early on - clients should expect their facilitators to ask about them all - and to help them work out the answers!

Challenging conversations

So to sum up, the facilitator will potentially challenge the client team about:

• Objectives • Context • Participants • Space • On-the-day process • Follow-up process

Free download

If you'd like to download a version of this, click here.

The neutral facilitator

So often, in our field, we find ourselves straddling roles: playing the facilitator role in a meeting when we (or the organisation we work for) has a preferred type of outcome in mind. A professional independent facilitator shouldn't have this problem: if your ability to stay out of the content is at risk because of strong personal opinions about the topic, then you don't take the job.

But if your organisation has, for example, an environmental or sustainability mission, then you may need to ensure that this mission is reflected in the group's conversation. Or if you are the sustainability lead in your organisation, you may want to ensure that colleagues challenge each other enough on environmental limits, ethics and social justice during internal workshops.

I have been spending a lot of time recently training people from organisations which clearly have an agenda, and yet where it definitely makes sense for staff to have good facilitation skills. The question of how to manage this 'agenda' dilemma has come up.

A lot of the reflection is on how they know when it would be appropriate or not for them to facilitate, what they do if they notice their own agenda coming to the fore and interfering with their facilitator role, and how to manage this tension in preparation and in the moment.

What are your options?

Don’t facilitate the meeting. Explain your conflict of interest and ask the meeting’s convenor, host or planning group to find an alternative facilitator.

Ask someone else to attend the meeting as a participant, who you know will ensure that your own interests are represented. For example, a colleague or someone from a similar organisation which shares your interests. This is a particularly useful strategy if it's important that someone champions being ambitious about strong sustainability.

Step out of role. If the conversation unexpectedly begins to cover topics in which you have an interest, tell the group that this has happened and ask their permission to temporarily step ‘out of role’ as facilitator. Have your say, and then clearly step back into role.

Flag the role conflict and ask the group to help you stay independent. Tell the group that your intention is to be a neutral facilitator, and that you positively welcome them flagging it up if they think you are not behaving in a neutral way.

What place knowledge?

Another kind of neutrality relates to knowledge of the topic under discussion. Facilitators often maintain that knowledge of the topic under discussion is not necessary, and I'd agree with that - with some caveats (see below).

Sometimes experts take on the facilitator role for reasons which seem obscure and probably stem from misunderstanding of facilitation skills and practices in the client's and expert's mind. (A senior Judge of my acquaintance was once asked to 'facilitate' a workshop session on his area of expertise. I was astounded! He is very expert and experienced: why would you ask him to put his specialist knowledge away and play the 'servant'. A waste of his skills. I can only imagine that the event organisers did not know what facilitators do, and used the word as a fashionable alternative to 'lead'.)

And sometimes clients opt for a facilitator who does have experience or knowledge of the topic, because they imagine this will make the person a better facilitator.

And I think they could be right!

When knowledge helps

There are a few, limited ways in which knowledge can help your facilitation, in my experience.

- Jargon and acronyms - If you are the only person in the room who doesn't know the technical language, and you need to have it explained to you, this can slow things down and irritate the group. If you are also acting as a scribe, then spelling things wrongly can undermine the trust the group has in you. Ask for a glossary as part of your briefing!

- Stick to the point - it can be hard to tell whether someone is wandering off from the aims of the discussion, if you don't know the subject. Is it irrelevant to talk about interference with sonar when discussing the environmental impact of wind turbines? (*) When discussing low-income customers, will discussing local currencies be time well spent? (#)

- Digging deeper - the flip side of not recognising whether someone is 'on topic' or not, is failure to spot important distinctions. If one participant talks about biofuels and the other about bioenergy, is this just a pleasant variety of words to avoid boredom, or a crucial distinction worth exploring? If you know a bit about the field, your guess is more likely to be a good one.

Caution! I do not intend to imply that you can assume your knowledge is sufficient to make these judgements on behalf of the group. If you think something may be off the point, you'd still want to check this out with the group because this is their decision. Knowing a bit helps you to make better guesses.

Download

There is a short download on this, here.

Discuss

Join in the discussion in the comments thread. There's also a very lively thread over at the IAF Linked-In group. If you're a member of that group, you can add your perspective here.

Answers

* No - there are concerns about bats being affected by turning blades, although whether sonar / echolocation is involved is unclear. So not irrelevant.

# Yes - if there is a viable local currency already established in an area, then this could well be a useful suggestion. So not irrelevant.

When form is content: singing a round

A great little place near me runs weekly group sessions where we reflect on our lives and work together on essential skills like empathy and dealing with difference. We also take part in experiential group activities*. Today's theme was trust: the necessity of continuing to trust each other, despite the frailties and failures we know we will sometimes experience. Partway through a presentation on this, we tried an experiment: singing a round. The song was one that many of us - but not all - had sung before.

The words are about joining together to make something bigger than the whole. And so is the form. We begin by singing in unison. Then we break into groups and each group begins the song slightly later than the previous group. The tune and words reveal themselves as elements which work together as the phrases overlap, making something more delightful and interesting than the unison version.

The rounds I learnt as a child (London's Burning, Frere Jacques) used the form for its entertainment value (!) but this song uses the form to deliver and emphasise content.

I wonder how we can do the same in our facilitation training...

*Yes, I'm being a little coy here. As a confirmed atheist, it's a little uncomfortable to explain how I love going to my local Unitarian church. Discovering that the Minister is also an atheist was a nice surprise. But there you go: my notions of church have been confounded, so check it out.

What is it afraid of, what's it trying to hide?

I've not blogged in months - too busy and too tired. But lately I'm emerging from bonkers levels of work and have the time and energy to read the papers. Even the review sections! This blog post is triggered by an interview with M John Harrison by Richard Lea in Saturday's Guardian. I like science fiction in a casual and (I'm afraid) ignorant way, including Margaret Attwood's speculative fiction set in eco-dystopias and Philip Pulman's theological atheist fantasy parallel universes. But I'm afraid I don't know M John Harrison's work.

What really struck me - and the reason I read the article - was the quote pulled out to headline it:

"A good rule of writing in any genre is: start with a form, then ask what it's afraid of."

In touch with fear

Some people are in touch with their anger, others with their guilt, a lucky few with their joy and exuberance. I'm very aware of my fear - although I don't always spot what's causing it at the beginning. (As a tangent: it may not be fear at all. In the same edition, Oliver Burkeman writes about physical symptoms being (mis)labelled as particular emotions.)

So I'm wondering about my own practice, and if it might be liberating to consider the form - the genre- and the fear that Harrison claims can exist outside the individual practitioner and in the form itself.

As a trainer and facilitator, and as a consultant, what are the genres I work in? And what are those genres afraid of? What are they trying to hide?

What's the genre?

First, define your terms. This will get too dull if I try to examine too many. So I'll stick to the designed, facilitated meeting. This is my stock-in-trade. The aims are untangled and combed through until they gleam with clarity, realism and honesty. The meeting is made up of sessions lined up in the optimum sequence. Attention is paid to ensuring a mix of modes (individual, pairs, small groups, whole group; spoken, written, thought, drawn; presented, discussed, explored, agreed and so on). We consider in advance what kind of record is needed, and what needs to be recorded in the room to make sure this happens. I could go on - at some length.

What is this form afraid of?

I think there are two principal fears. It's afraid of wasting people's time and it's afraid of people hiding things which - when shared - are important for mutual understanding and progress. These seem like right and proper things to want to avoid.

There may be some other fears, which are worth examining and asking - in Harrison's words - "what it's trying to hide".

What's it trying to hide?

The genre of the planned facilitated meetings may be trying to hide things about itself, or about the people involved in making it happen. I'll return to this question in due course, but find myself stumped for the moment!

Facilitation training - can it work one-to-one?

I love to train people in facilitation skills. It's so much fun! People get to try new things in a safe environment, games are played, there's growth and challenge, fabulously supportive atmospheres can build up.

What's the minimum group size for this kind of learning?

How about one?

A group of one

From time to time I'm approached by people who want to improve their facilitation skills, but who don't have a ready-made group of colleagues to train with. I point them towards open courses such as those run by the ICA, and let them know about practice groups like UK Facilitators Practice Group. And sometimes, I work with them one-to-one.

This one-to-one work can also happen because a client doesn't have the budget to bring in facilitator for a particular event, and we agree instead to a semi-coaching approach which provides intensive, just-in-time preparation for them to play the facilitator role. This is most common in the community and voluntary sector.

The approach turns out to be a mix of process consultancy for specific meetings, debriefing recent or significant facilitation experiences, and introducing or exploring tools and techniques.

Preparing to facilitate in a hierarchy

A client had a particular event coming up, where she was going to be facilitating a strategy session for a group of senior people from organisations which formed the membership of her own organisation. She had concerns around authority: would they accept her as their facilitator for this session? She was also keen to understand how to agree realistic aims for the session, and to come up with a good design.

We spent a couple of hours together, talking through the aims of the session and what she would do to prepare for it. We played around with some design ideas. I introduced the facilitator's mandate, and she came up with ways of ensuring she had a clear mandate from the group which she could then use to justify - to them and to herself - taking control of the group's discussions and managing the process. Helped by some coaching around her assumptions about her own authority, she came up with some phrases she was comfortable using if she needed to intervene. We role-played these. She felt more confident about the framework and that the time and energy we'd put into the preparation was useful.

Facilitation skills as a competence for engaging stakeholders

As part of a wider team, I've been working with a UK Government department to help build their internal capacity for engaging stakeholders. As a 'mentor', I worked with policy teams to help them plan their engagement and for one team, this included helping a team member get better at meeting design and facilitation. He already had a good understanding of the variety of processes which could be used and a strong intuitive grasp of facilitation. We agreed to build this further through a (very short) apprenticeship approach. We worked together to refine the aims for a series of workshops. I facilitated the first and he supported me. We debriefed afterwards: what had gone well, what had gone less well, and in particular what had he or I done before and during the workshop and what was the impact. He facilitated the next workshop, with me in the support role. Again we debriefed. We sat down to plan the next workshop, and I provided a handout on carousel, which seemed like an appropriate technique. I observed the next two workshops, and again we debriefed.

Instead of a training course

I worked with a client who wanted to develop his facilitation skills and was keen to work with me specifically, rather than an unknown and more generic open course provider. I already knew his context and he knew I'd have a good appreciation of some of his specific challenges: being in the small secretariat of what is essentially an industry leadership group which is trying to lead a sustainability agenda in their sector. His job is to catalyse and challenge, as well as to be responsive to members. So when he is planning and facilitating meetings, he will sometimes be in facilitator mode and sometimes he will need to be advocating a particular point of view.

Ideally, I'd have wanted to observe him in action in order to identify priorities and be able to tailor the learning aims. But the budget didn't allow for this.

We came up with a solution which was based on a series of four two-hour sessions, where I would be partly training (i.e. adding in new 'content' about facilitation and helping him to understand it) and partly coaching (i.e. helping him uncover his limiting assumptions and committing to do things differently). The sessions were timed to be either a bit before or a bit after meetings which he saw as significant facilitation challenges, so that we could tailor the learning to preparing for or debriefing them. The four face-to-face sessions would be supplemented by handouts chosen from things I'd already produced, and by recommended reading. We agreed to review each session briefly at the end, for the immediate learning and feedback to me, and partly to model active reflection and to get him into the habit of doing this for his own facilitation work.

In our initial pre-contract meeting, we agreed some specific learning objectives and the practicalities (where, when). Before each session, we had email exchanges confirming what he wanted to focus on. This meant I could prepare handouts and other resources to bring with me.

And this plan is pretty much what we ended up doing.

He turned out to be very well suited to this way of learning. He was a disciplined reflective practitioner, making notes about what he'd learnt from his experiences and bringing these to sessions. He was thoughtful in deciding what he wanted to focus on which enabled me to prepare appropriately. For example, in our final session he wanted to look at his overall learning and to identify the learning edges that he would continue to work on after our training ended. We did two very different things in that session: he drew a timeline of his journey so far, identifying significant things which have shaped the facilitator he is now. And we used the IAF's Foundational Facilitator Competencies to identify his current strengths and learning needs.

Can it work?

Yes, it's possible to train someone in facilitation skills one-to-one. This approach absolutely relies on them have opportunities to try things out, and is very appropriate when someone will be facilitating anyway - trained or not. The benefits are finely tailored support which can include advice as well as training, coaching instead of 'talk and chalk', and debriefing 'real' facilitation instead of 'practice' session.

There are downsides, of course. You don't get the big benefit which can come from in-house training, where a cohort of people can support each other in the new way of doing things and continue to reflect together on how it's going. And you don't get the benefit of feedback from multiple perspectives and seeing a diverse way of doing things, which you get in group training.

But if this group approach isn't an option, and the client is going to be facilitating anyway, then I think it is an excellent approach to learning.

Occupy movement: the revolution will need marker pens

On my bike, between meetings last week, I was passing St Paul's Cathedral in London so I wandered through the Occupy London Stock Exchange 'tent city'. Occupy LSX has divided opinion. At the meeting I was going to - a workshop of organisational development consultants, facilitators, coaches - some people made rather snide remarks about the likely impact of the first cold weather on the protesters, and about unoccupied tents. There's a retort here about the infamous thermal imaging scoop. Others were interested in and sympathetic to the dissatisfaction being expressed, but frustrated by the lack of a clear 'ask' or alternative from the occupiers.

Emergent, self-organising, asks and offers

What struck me, however, were the similarities between the occupy area itself, and some really good workshops I've experienced. There was plenty of space given aside for 'bike rack', 'grafitti wall' and other open ways of displaying messages, observations or questions. There was a timetable of sessions being offered in the Tent City University, and another board showing the times of consensus workshops and other process-related themes.

There was a 'wish list' board, where friendly passers-by could find out what the protesters need to help keep things going. Marker pens and other workshop-related paraphernalia are needed, as well as fire extinguishers and tinned sweetcorn.

I saw these as signs of an intentionally emergent phenomenon, with a different kind of economy running alongside the money economy. Others have blogged about the kinds of processes honed and commonly in use at this kind of event or camp, in particular if you're interested there's loads on the Rhizome blog.

Don't ask the question if you don't already know the answer?

I recognise the frustration expressed by some of my OD colleagues about the lack of clearly-expressed alternatives. This kind of conversation often occurs in groups that I facilitate: someone (often not in the room) has expressed a negative view about a policy, project or perspective. The people in the room feel defensive and attack the grumbler: "I bet they couldn't do any better" or "what do they expect us to do?". Some management styles and organisational cultures are fairly explicit that they don't want to hear about problems, only solutions. (Browsing here gives some glimpses of the gift and the shadow side of this approach.)

But I see something different here: a bottom-up process where people who share broadly the same intent and perspective, come together to explore and work out what they agree about, when looking at the problems with the current situation and the possible ways of making things better. The are participatively framing a view of the system as it is now, and what alternatives exist. This takes time, of course.

They are also, as far as I can tell from the outside, intentionally using consensus-based processes rather than conventional, top-down, leader-led or expert-led processes to organise this. Understandably frustrating for the news media which rely increasingly on short sound-bites and simple stories with two sides opposing each other. And it could get very interesting when the dialogue opens up to include those who have quite different perspectives on "what's really going on here" (for example mainstream economists, bankers, city workers).

The other thing I notice about this expectation of a ready-made coherent answer, is how similar it is to some group behaviour and the interventions made by inexperienced facilitators and coaches. When I am training facilitators, we look at when to intervene in a group's conversation, particularly when to use the intervention 'say what you see'. (This makes it sound very mechanical - of course it's not really like that!)

The trainee facilitator is observed practising, and then there is feedback and a debriefing conversation. Perhaps they chose not to intervene by telling the group what they observed. Sometimes during this feedback and debrief, a trainee will say something like "Yes, I noticed that, but I didn't want to say anything because I wasn't sure what to do about it or what it meant." They are assuming that you can only 'say what you see' if you know what it means and already have a suggestion about what to do about it.

But it also serves a group to say what you see, when you haven't a settled interpretation or clear proposal. (In fact, it is more powerful to allow the group to interpret, explain and propose together.) All questions are legitimate, especially those to which we don't (yet) know the answer. Ask them. Guess some answers. And this - for the time being - is what the occupy movement is doing.

The revolution will need marker pens

All this consensus-based work and open-space style process needs plenty of marker pens (permanent and white-board). So if you have a bulging facilitation toolkit and you're passing St Paul's, you know what to do!

Update

Others have spotted these connections too. Listen to Peggy Holman talking about Occupy Wall Street on WGRNRadio, 9th January.

Finding the house keys

I facilitated a workshop once, where everyone knew that they wanted to work together on something, but they didn't know what. They were all lawyers of one kind or another: barristers in private practice, in-house legal eagles for NGOs, members of the judiciary. They shared an interest in human rights and climate change. They shared a suspiscion that existing human rights legislation (including conventions) and existing courts which hear human rights cases (including some international ones) might be a good way to take forward cases which would catalyse action to reduce emissions and ensure victims of the impact of climate change get proper help.

During the workshop they shared information and stories, hoping that they would find one exciting thing to work on which had real potential. They discussed the detail of different legal approaches, what a perfect case would need to look like, the pros and cons of bringing cases in different jurisdictions.

As the workshop went on through its first day and towards lunch on the second day, they still hadn't found it.

And then suddenly they had!

How did that happen?

What did they do to find the focus? What did I do to help?

I don't know. Nothing different than we had been doing for a day and a half.

Bingo!

It was like that moment when you find the house keys. We had been looking and looking in all the right places and all the right ways. It wasn't that we started looking better just before we found them. It's just that we finally found them.

(It's funny how they're always in the last place you look.)

Reflections after workshops – catching the learning

My client drove me to the station from our rather remote venue this afternoon. She said:

"Do you think about a workshop after it's over, or..."

I mentally completed her sentence as "or don't you manage to?" After a small pause, she finished

"...or are you able to let it go?".

I was reminded of the usefulness of not assuming you know what someone else is going to say.

And I realised I'd filled the pause with my own self-criticism: because I'm intellectually committed to action/reflection, and thinking about a workshop after it's over is a powerful reflection stage.

But sometimes I'm just too tired to concentrate on reflecting 'properly'. And I might beat myself up about all the scintilating learning I'm missing by not journalling or even blogging as much as I might.

Instead, my mind wanders or I retreat into the self-indulgence of a journey home where I can read the paper, mess up the Kakuro or stare out of the window.

But this particular journey home has been longer than expected, and I've got my second wind. So I will 'reflect properly', drawing on what we talked about and thought about on the way to the station.

You're working too hard

One of the things my assessors said after my CPF earlier this year was that I was working too hard. The group should be doing the work, I need to get out of their way. Perhaps I can take the same advice about reflection on my facilitation: let my mind do the work and get out of its way.

Wandering mind

The drive to the station was quite long, so I did let my mind wander, sparked by my client's question. We had one of those leisurely conversations which are interspersed with gentle silences. And our conversation touched on spaces, client comfort and workshop plans.

Owning the space

My mind wandered to what we had done to own the space. This workshop was the third in a series of three and all the venues we used had their challenges. Two of the three lacked good smooth walls to stick flips on and write on. Today's was crowded and we had to prop up boards on tables and stacked chairs to be able to see the flips.

In every venue, we quickly assessed the room, decided which furniture to move around or move out of the room altogether, and worked out where we would display the flips we needed for various metaplanning-type exercises and for participants to be able to see the running record.

Over the years, I have had to learn about the importance of layout, gain the confidence to take responsibility for making spaces as good as they can be for the conversation we want to have, pick up some tips and tricks for improvising the space and equipment needed, and get more decisive about making changes rapidly. That experience has paid off today.

Over-identifying with the client: whose comfort?

I have been more conscious recently of my own tendency to over-identify with my client, when facilitating stakeholder workshops. I feel uncomfortable when I think the client team may be feeling uncomfortable. I feel relieved when I think they may be feeling relieved.

I'm confident that this is not having a significant effect on my facilitation, but I'm conscious that this is a danger and that I need to check my inner motivation when choosing to intervene (or not) in situations where I believe that I know what my client would like to hear. Holding the space in periods of discomfort, doubt, uncertainty, conflict, anger, disappointment - this is one of the special gifts which a facilitator can bring to a group, and I'd like to strengthen my ability to do this with ease, without being overly concerned about the client's level of comfort.

As it happens, today I was impressed with how well the client team responded to some of the things stakeholders said, which were probably hard for them to hear. Defensiveness was mostly absent. When the team thanked people for sharing their experiences, perspectives, frustrations and aspirations, I think they meant it.

If I had, even unconsciously, sheilded the client from this difficult conversation, then I might have avoided some temporary discomfort (largely my own?) but I would have prevented some important truth-telling and mutual understanding from emerging. And the elephants in the room would have remained hidden in plain view.

Let go of the plan

In two of the three workshops, we radically redesigned the agenda part way through the day. A wise facilitator once said to me that any fool can design a workshop, it's being able to redesign on the hoof that is the mark of greatness. I wouldn't claim to greatness, but my redesigns were good calls!

Today's was helped enormously by the intervention during lunch of a process-savvy participant who observed that what the organising team wanted to talk about was not what the participants wanted to talk about. We negotiated a 'deal' to split the afternoon's work so that some time was spent on the more pedestrian but urgent client concerns (and the group threw themselves into this) but a larger chunk of time was allocated to some open space. This was agreed by the rest of the group.

As my client and I discussed this on the way to the station, I was reminded of some insights about planning.

- At this AMED event last Friday, we talked in passing about Eisenhower's claim that "plans are useless but planning is indispensible."

- A few days before, at an ODiN workshop organised by Chris Rodgers, someone talked about their frustration at hearing people use 'opportunistic' as a way of disparaging those charities which apply for funding without a nailed down strategic plan.

- And my reading of this new sustainability leadership book containing experiences written through an action research lens has helped me understand how intention, values and an understanding of what you feel drawn to do can be coupled with being alert to opportunity resulting in emergent strategy. (There's an explanation of emergent strategy here, but you may know of a better one - stick it in the comments.)

I think there's a parallel here with workshop (re)design:

- some values underpinning your work as a facilitator,

- some shared aims (intentions) agreed with participants,

- an understanding of the expertise and resources (e.g. time, space, numbers of different kinds of people, access to information) available for the conversation.

- being alert to 'what's trying to happen here' and getting out of its way.

If you have those things - as a result of doing some planning (having a conversation about planning) - then a strategy is able to emerge if you get out of its way.

Update: This today (1st October 2011) from Dave Pollard would call this resilience planning, rather than strategic planning. An interesting post.

The conversation goes where it goes - who knows what might have happened if...

What I didn't follow up on was the confession which may have been present in my client's question: does she find herself unable to let go after a workshop, dwelling on what might have been in a way which doesn't help her learn but perhaps keeps her in that unconfident phase of believing that she hasn't done well enough?

I don't know. That conversation may have been equally rich. The coach in me would have gone down that route, but the coach in me was taking some time out.

But by not trying too hard, and offering my own meandering observations, I reflected properly on what I'd learnt from the day.

What if our conversations were deep, open?

I've met some interesting and challenging facilitators recently who have helped me reframe and explore my facilitation work and my sustainable development aims. Our conversations together have been so refreshing and enriching, we wondered if it might be possible to open them up to a wider group...

So we have created Deep Open.

It's a one-day workshop for people who are interested in groups, conversation, change and sustainable development. We hope to enable conversations which allow us to be aware of our feelings (physical and emotional), alert to difference and conflict, challenging and honest. We're going to experiment with having our feelings rather than letting our feelings have us. We're going to experiement with not distracting ourselves when things feel uncomfortable. We're going to try to resist being task-focussed, whilst staying together with purpose.

If you are intruiged by this - rather than irritated - then you might want to join us on 19th May in London for this workshop.

We're running the event in conjunction with AMED. The others involved are Johnnie Moore, Debbie Warrener and Luke Razzell.