When you're collaborating, there are six characteristic challenges you're bound to come up against. This is the third.

Second characteristic: decisions are shared

Characteristics of collaborative working, episode one of six

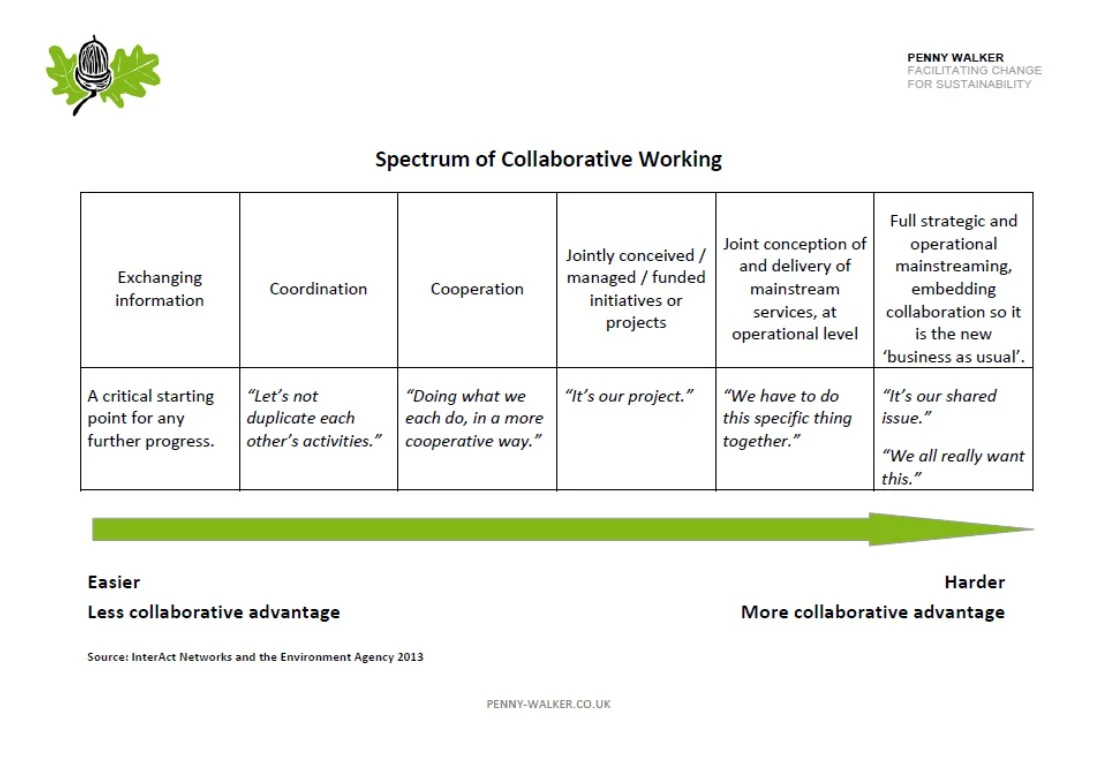

It's not all or nothing - there's a spectrum of collaborative working

Does collaboration sound like too much hard work? The examples of collaboration which get most attention are the big, the bold, the game changing.

Which can be a bit off-putting. If I collaborate, will I be expected to do something as hard and all-consuming?

Actually, most collaborative work is much more modest. And even the big and bold began as something doable.

So what kind of work might collaborators do together?

Collaborative Advantage

Collaborative Advantage needs to exist, in order for the extra work that collaborating takes to be worth it! My colleague Lynn Wetenhall puts it like this, in training and capacity building we've developed for the Environment Agency:

"Collaborative advantage is the outcomes or additional benefits that we can achieve only by working with others."

Know when to collaborate...

When contemplating collaborating, you need to make at least an initial cost-benefit judgement and this relies on understanding the potential collaborative advantage. Chris Huxham in Creating Collaborative Advantage waxes rather lyrical:

“Collaborative advantage will be achieved when something unusually creative is produced – perhaps an objective is met – that no organization could have produced on its own and when each organization, through the collaboration, is able to achieve its own objectives better than it could alone.”

But it’s even better than that!

Huxham goes on:

“In some cases, it should also be possible to achieve some higher-level … objectives for society as a whole rather than just for the participating organizations.”

So collaborative advantage is that truly sweet spot, when not only do you meet goals of your own that you wouldn’t be able to otherwise, you can also make things better for people and the planet. Definitely sustainable development territory.

...and when not to

There’s another side to the collaborative advantage coin.

If the potential collaborative advantage is not high enough, or you can achieve your goals just as well working alone, then it may be that collaboration is not the best approach.

DareMini

So DareConfMini was a bit amazing. What a day. Highlights:

- Follow your jealousy from Elizabeth McGuane

- Situational leadership for ordinary managers from Meri Williams

- The challenge of applying the great advice you give to clients, to your own work and practice from Rob Hinchcliffe

- Finding something to like about the people who wind you up the most from Chris Atherton

- Being brave enough to reveal your weaknesses from Tim Chilvers

- Jungian archetypes to help you make and stick to commitments from Gabriel Smy

- Radical challenges to management orthodoxy from Lee Bryant

- Meeting such interesting people at the after party

No doubt things will continue to churn and emerge for me as it all settles down, and I'll blog accordingly.

In the meantime, all the videos and slides can be watched here and there are some great graphic summaries here (from Francis Rowland) and here (from Elisabeth Irgens)

There are also longer posts than mine from Charlie Peverett at Neo Be Brave! Lessons from Dare and Banish the January blues – be brave and get talking from Emma Allen.

If you are inspired to go to DareConf in September, early bird with substantial discounts are available until 17th February.

Many thanks to the amazing Jonathan Kahn and Rhiannon Walton who are amazing event organisers - and it's not even their day job. They looked after speakers very well and I got to realise a childhood fantasy of dancing at Sadler's Wells. David Caines drew the pictures.

Don't be an expert - at least, not yet

The trouble with being an expert is that you are expected to come up with solutions really fast. Or you think you are. Doubly so if you're an advocate or a campaigner. You can be tripped up by your own assumptions about your role, and stumble into taking a position much too early. And once you've taken a position, it feels hard to climb down from it and explore other options.

Which can be a big mistake.

Don't be an expert, yet

Pretty much every project you'll ever work on has more than one noble aim (or, at least, more than one legitimate aim). On time, on budget. For people, profit and planet. Truth and beauty.

Not much point designing the shiniest, coolest, sexiest thing that can't be built. Or the safest, most ethical, handcrafted whoosit that's too expensive for anyone to buy. Or running an organic, fair trade eco-retreat which can only be reached by helicopter.

If a critical variable needs to 'lose' in order that the thing you have committed yourself to can 'win', you've set it up wrong.

Why set it up as a zero-sum game, when it could be that there's a win-win solution enabling everyone to get everything they want? (I could tell you about boogli fruit, but once again I'd have to kill you.)

Not everything is a fight

If you frame it as a fight, you'll get a fight. If you frame it as a complex problem with a mutually-beneficial solution that hasn't been found yet - you may just get it.

But how can you help the conversation be a dialogue rather than a gun-fight?

You need to stay in that uncomfortable place of not knowing. Listen well. Ask questions.

Above all, maintain an attitude of respect, curiosity and trust.

Want to explore further?

I'll be talking more about this at #DareConf Mini on 20th January - still time to join me and some awesome speakers.

And here's a New Year's gift to help: £100 off if you use code PENNY when booking.

Deadlines

Do deadlines help a group reach consensus? Or do they get in the way? Yesterday brought the news that the latest round of talks in the peace process in Northern Ireland had broke up without agreement, the deadline having passed. There's a report from the BBC here.

I make no comment on the content of the talks, but I am interested in the process. Why was this particular deadline set? And do deadlines help by providing a sense of jeopardy - a time when the Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement comes into play? Or by restricting the time for exploration and low-anxiety creativity, do they get in the way of positive consensus?

Deadlines for discussion and agreement may be tied to objective events in the real world: mother and midwife need to agree how to manage labour before it happens. They may be tied to objective but less predictable events: the Environment Agency and the stakeholders discussing details of the Medmerry Managed realignment flood defence scheme wanted to get it built in time to protect the area from the higher risk of winter storms and flooding. Or they may be tied to other events which are choices rather than unstoppable events, but ones where choosing not to meet the deadline would have very large consequences: the Environment Agency and the Olympic Delivery Authority needed to agree how to handle drainage and water quality from the Stratford Olympic site in time for the games to happen in 2012.

I may be missing something, but the Haass talks don't seem to have any of these justifiable external pressures. So why the deadline?

Location, location, location

Picture the scene: the room, which you haven't been able to check out before, has a low ceiling, tiny windows that somehow don't manage to let in much light, and is decorated in shades of brown and purple. There are uplighters on the walls, which have large strategically placed paintings screwed to them. And, of course, you have been told that under no circumstances can blu-tack be used on the rough-textured wallpaper.

A moment of commitment - reflections on writing

Tempting and disconcerting in equal measure: being asked to write a book is such a flattering thing, dangerously seductive; being asked to write a book is such a frightening thing, because "what if it's rubbish?" Putting something in writing is a moment of commitment: hard for an inveterate hedger and fence-sitter like me. (I couldn't even decide between 'hedger' and 'fence-sitter', could I?)

Avoiding temptation, taking courage

In an attempt to stop it being rubbish, and to remind myself that it's not me that's being flattered - it's the wise things I've learnt from others - I made a conscious choice to stand on shoulders of giants both for theory and for tips that really make a difference, when writing Working Collaboratively.

I found some great academic research and theory before I decided that I really needed to stop reading and get on with writing. But it was more on 'collaborative governance' (advising others on how to do things) than multi-sector collaboration to get things done. Noticing that distinction helped me decide what to get my teeth into.

What kind of collaboration?

I knew I wanted to include examples, and there were plenty out there even from a cursory look. But I wanted to find ones which were more than contractual, more than cause-related marketing, and which involved multiple collaborators not just two (you can't change a system with just two players). I wasn't so interested in crowd-sourcing, where the hive mind is used to generate multiple clever ideas which might be the solution, but stops short of putting collaborative solutions into practice. That feels like another form of consultation to me.

It's not to say these are bad things: but to me they are less difficult and less necessary than when collaboration is a way to solve system-level wicked problems, where there is a need for simultaneous action by players who each bring a different piece of the jigsaw with them.

So I drew up some criteria and then searched for examples which both met those criteria and that I had a head-start with: knowing key players, for example, who I could be confident would at least read my email or return my call.

Hearty thanks to everyone who made time to be interviewed or to give me their perspective on some of the examples.

Book writing as a project

The project has followed a pattern I'm now pretty familiar with, in my consulting, training and facilitation work:

- excitement and disbelief at being invited to do such a cool thing;

- fear that I'll have nothing interesting or useful enough to say;

- writing myself a little aide memoire to keep those pesky internal voices at bay;

- mind mapping key points and allocating word count (in a training or facilitation situation, that would allocating minutes!);

- less familiar was the long research phase, which is not something have to do very often and was a real luxury;

- identifying examples and interviewees.

Then the actual creativity begins: knitting new things, finding scraps of existing articles, handouts or blogs to recycle and stitching it together like a quilt with additional embroidery and applique. I start committing myself to a narrative thread, to a point of view, to some definitive statements.

Then the first of many moments of truth: sending the draft off and nervously awaiting the feedback - sitting over my email until it arrives and then putting off the moment of actually opening it and reading the response.

Altering and amending the draft in response to that feedback and to my own nagging unhappiness with how I've captured something which may be very hard to pin down.

And then there's a dip: the boredom as I get too familiar with the material: is there anything new here? Will anyone else find it interesting?

At that point I know I need to leave it all to settle for a bit and come back to it fresh after some weeks. Fortunately, when I did, I felt "yes, this is what I wanted to say, this is how I wanted to say it" and crucially: "this has got things in it that readers will find useful, amusing, novel, easy to understand."

Collaboration of goodwill

It's sobering and enlightening to remember how much goodwill was involved - interviewees, people who gave me permission to use models and frameworks; anonymous and other reviewers; people helping to get the word out about it. There was a lot of swapping favours and continuing to build and reinforce working relationships. It might be possible to analyse these all down to hard-nosed motivations, but I think much of it was trust-based and fuelled by enthusiasm for the topic and a long history of comfortable working relationships.

What did I say?

As an author, it feels as if the project is ended when the final proofs go back to the publisher. But of course it doesn't, thankfully, end there. Now that I've been invited to blog, present or share expertise off the back of the book (e.g. Green Mondays, MAFN, DareConf) I have to remind myself of what I've written! Because your thinking doesn't stand still, nor should it.

What you need from your facilitator, when you're collaborating

Researching Working Collaboratively, I heard a lot about the importance of a skillful facilitator. And you can see why. Collaboration happens when different people or organisations want to achieve something - and they need common ground about what it is they want to achieve. They might both want the same thing or they may want complementary things. Since finding common ground is not easy, it's good to know facilitators can help.

Common ground, common process

But it's not just common ground on the goals that need to be achieved, it's common ground on the process too. It's essential to be able to find ways to work together (not just things to work together on).

Process can be invisible - you're so used to the way your own organisation does things, that you may not see that these processes are choices. And it's possible to choose to do things in other ways.

This can be as simple as using descriptive agendas (which set out clearly what the task is for each item e.g. 'create a range of options', 'discuss and better understand the options', 'identify the group's top three options', 'agree which option to recommend', 'agree which option to take forward') rather than the more usual summary version (Item 1: options).

Or it might be agreeing to set up special simultaneous consultation and decision mechanisms within each of the collaborating organisations rather than each one going at its own usual, different, pace.

To be able to make these choices, process needs to be brought to conscious awareness and explicitly discussed. This will be a key part of any facilitator's role.

Disagreement without conflict

Collaboration is about agreement, of course. But if the organisations have identical aims and ways of meeting them, then they might as well merge rather than collaborate! In collaboration, you must also expect disagreement and difference.

Sometimes people may be so keen to find the common ground, that discussing the areas of disagreement and difference becomes taboo. Much more healthy is being able to discuss and acknowledge difference in an open and confident way. A facilitator who is used to saying: "I notice that there is a difference of view here. Let's understand it better!" in a perky and comfortable way can help collaborators be at ease with disagreement.

Building trust

Your facilitator will also need to help you be open about the constraints and pressures which are limiting your ability to broaden the common ground about desired outcomes or process. Perhaps a public body cannot commit funds more than one year ahead. Perhaps a community or campaign group needs to maintain its ability to be publicly critical of organisations it is collaborating with. A business may need to be able to show a return on investment to shareholders. In most cases, the people 'in the room' will need to take some provisional decisions back to their organisation for ratification.

Just like the areas of disagreement, these constraints can be hard to talk about. Some clients I work with express embarrassment bordering almost on shame when they explain to potential collaborators the internal paperwork they 'must' use on certain types of collaborative project.

Much better to be open about these constraints so that everyone understands them. That's when creative solutions or happy compromises arise.

A neutral facilitator?

Do you need your facilitator to be independent, or do they need to have a stake in the success of the collaboration? This is the 'honest broker / organic leader' conundrum explored here.

I have seen real confusion of process expertise and commitment to the content, when collaborative groupings have been looking for facilitation help. For example, the UK's Defra policy framework on the catchment based approach to improving water quality seems to assume that organisations will offer to 'host' collaborations with minimal additional resources. If you don't have a compelling outcome that you want to achieve around water, why would you put yourself forward to do this work? And if you do, you will find it hard (though not impossible) to play agenda-neutral process facilitator role. There is a resource providing process advice to these hosts (Guide to Collaborative Catchment Management), but I am not sure that any of them have access to professional facilitation.

This is despite the findings of the evaluation, which say that facilitation expertise is a 'crucial competency':

"Going forward, pilot hosts indicate that funding, or in-kind contribution, for the catchment co-ordinator and independent facilitation roles is essential." (p8)

And Defra's own policy framework makes clear that involving facilitators is crucial to success:

"Utilising expert facilitation to help Partnerships address a range of issues for collaborative working including stakeholder identification and analysis, planning meetings, decision-making and engaging with members of the public [is a key way of working]."

There seems to be some understanding of the agenda-neutral facilitation role, but a lack of real answers to how it will be resourced.

I will be fascinated to see how this plays out in practice - do comment if you have experience of this in action.

How can I get them to trust me?

Trust is essential to collaborative work and makes all kinds of stakeholder engagement more fruitful. Clients often have 'increased trust' as an engagement objective. But how do you get someone to trust you?

Should they?

My first response is to challenge back: should people trust you? Are you entering this collaboration or engagement process in good faith? Do you have some motives or aims which are hidden or being spun? Do some people in your team see consultation and participation as just more sophisticated ways of persuading people to agree with what you've already made up your mind about? Or are you genuinely open to changing things as a result of hearing others' views? Is the team clear about what's up for grabs?

It's an ethical no-brainer: don't ask people to trust you if they shouldn't!

Earn trust

Assuming you do, hand on heart, deserve trust, then the best way to get people to trust you is to be trustworthy.

Do what you say you're going to do. Don't commit to things that you can't deliver.

Don't bad-mouth others - hearing you talk about someone one way in public and another in a more private setting will make people wonder what you say about them when they're not around.

Trust them

The other side of the coin is to be trusting. Show your vulnerability. Share information instead of keeping it close. Be open about your needs and constraints, the pressures on you and the things that you find hard. If you need to give bad news, do so clearly and with empathy.

Give it time

Long-term relationships require investment of time and effort. Building trust (or losing it) happens over time, as people see how you react and behave in different situations.

Be worthy of people's trust, and trust them.

Summer round up

Sorry I haven't been over at this blog properly for a while: I've been busy blogging elsewhere to tell people about Working Collaboratively. Here's a round-up of the other places where I've been writing.

Blogtastic

Guardian Sustainable Business Collaborating can be frustrating but it isn't about sublimating your organisation's goals – it's about discovering common ground...

Business Green It's time for business to gang up on the barriers to change. Businesses need to collaborate with NGOs, communities and the public sector to make serious change happen... (To read this one, you will need to be a Business Green subscriber or register for a free trial.)

Forum for the Future / Green Futures Blog Shipping leaders look for common ground. Change in the shipping system will depend on time, trust and an independent third party...

Defra's SD Scene Newsletter Who might collaborate with you? The book contains frameworks, tools and interviews with people who have collaborated to achieve sustainable development outcomes, including from one of Defra’s recent Catchment Based Approach pilots to improve river health and water quality.

CSR Wire Finding the Dots: Why Collaborate When We Have Nothing In Common? When the problem is intractable, systemic and locked-in, it’s the very people you think you are in competition with who you need to listen to with the closest attention and the most open mind.

I've enjoyed the challenge of finding new angles on the same basic messages. I hope you enjoy reading them.

Amazonian

Mixed feelings on seeing that the book is now available on Amazon, too. You can get it as an ebook or paperback. I'm not sure how good Amazon's record is in collaborating for sustainable development goals... But at least there's a review function so people could share their thoughts on this paradox through that forum.

Collaborate: over and over again.....

One of the points that I end up stressing in collaboration training, and try to get across in the book, is the iterative nature of collaboration. Working Collaboratively is organised around three 'threads': what, who and how. 'What' is the compelling outcome you want to achieve, 'who' are the collaborators and 'how' is your process or ways of working. And you could think of these three threads being plaited together, because they are inseparable and they continue to need attention in parallel.

The 'over and over again' iteration happens for all three threads. As you explore shared or complementary outcomes, potential collaborators get closer or move away. As it becomes clearer who the collaborators will be, ways of working which suit them emerge or need to be thrashed out. As process develops, greater honesty and trust enables people to understand better what they can achieve together.

Plaited loops

So these three plaited threads (who, what, how) loop the loop as you go forwards - being reviewed and changed.

We explored putting in a graphic to illustrate this, but my idea couldn't be transferred to an image successfully. My very poor sketch will have to suffice.

Why does this matter?

Exploratory, tentative and above all slow progress can be exasperating not just for the collaborators but for their managers or constituencies. What's going on? Why aren't there any decisions yet? What are you spending all this time on, with so little to show for it? The investment in having what feels like the same conversation over and over again is essential. Collaborators need to appreciate that, and so do the people they report to.

“Working Collaboratively: A Practical Guide to Achieving More” Use PWP15 for 15% discount.

I learn it from a book

Manuel, the hapless and put-upon waiter at Fawlty Towers, was diligent in learning English, despite the terrible line-management skills of Basil Fawlty. As well as practising in the real world, he is learning from a book. Crude racial stereotypes aside, this is a useful reminder that books can only take us so far. And the same is true of Working Collaboratively. To speak collaboration like a native takes real-world experience. You need the courage to practise out loud.

The map is not the territory

The other thing about learning from a book is that you'll get stories, tips, frameworks and tools, but when you begin to use them you won't necessarily get the expected results. Not in conversation with someone whose mother tongue you are struggling with, and not when you are exploring collaboration.

Because the phrase book is not the language and the map is not the territory.

Working collaboratively: a health warning

So if you do get hold of a copy of Working Collaboratively (and readers of this blog get 15% off with code PWP15) and begin to apply some of the advice: expect the unexpected.

There's an inherent difficulty in 'taught' or 'told' learning, which doesn't occur in quite the same way in more freeform 'learner led' approaches like action learning or coaching. When you put together a training course or write a book, you need to give it a narrative structure that's satisfying. You need to follow a thread, rather than jumping around the way reality does. Even now, none of the examples I feature in the book would feel they have completed their work or fully cracked how to collaborate.

That applies especially to the newest ones: Sustainable Shipping Initiative or the various collaborators experimenting with catchment level working in England.

Yours will be unique

So don't feel you've done it wrong if your pattern isn't the same, or the journey doesn't seem as smooth, with as clear a narrative arc as some of those described in the book.

And when you've accumulated a bit of hindsight, share it with others: what worked, for you? What got in the way? Which of the tools or frameworks helped you and which make no sense, now you look back at what you've achieved?

Do let me know...

Working collaboratively: world premiere!

So it's here! A mere nine months after first being contacted by Nick Bellorini of DōSustainability, my e-book on collaboration is out!

Over the next few weeks, I'll be blogging on some of the things that really struck me about writing it and that I'm still chewing over. In the meantime, I just wanted to let you know that it's out there, and you, dear reader, can get it with 15% off if you use the code PWP15 when you order it. See more here.

It's an e-book - and here's something cool for the dematerialisation and sharing economy geeks: you can rent it for 48 hours, just like a film! Since it's supposed to be a 90 minute read, that should work just fine.

Thanks!

And I couldn't have done it without the wonderful colleagues, clients, peers, critics, fellow explorers and tea-makers who helped out.

Andrew Acland, Cath Beaver, Craig Bennett, Fiona Bowles, Cath Brooks, Signe Bruun Jensen, Ken Caplan, Niamh Carey, Lindsey Colbourne, Stephanie Draper, Lindsay Evans, James Farrell, Chris Grieve, Michael Guthrie, Charlotte Millar, Paula Orr, Helena Poldervaart, Chris Pomfret, Jonathon Porritt, Keith Richards, Clare Twigger-Ross, Neil Verlander, Lynn Wetenhall; others at the Environment Agency; people who have been involved in the piloting of the Catchment Based Approach in England in particular in the Lower Lee, Tidal Thames and Brent; and others who joined in with an InterAct Networks peer learning day on collaboration.

What your facilitator will ask!

So you've decided that the meeting or workshop you have in mind needs an independent, professional facilitator. You call them up and guess what? They start asking all these awkward questions. What's that about?

Facilitators don't just turn up and facilitate

Facilitated meetings are increasingly popular, and many teams and project groups understand the benefits of having their workshop facilitated. More and more organisations are also wanting to have meaningful, productive conversations with stakeholders, perhaps even deciding things together and collaborating. Facilitated workshops can be a great way of moving this kind of thing forward. But facilitators don't just turn up and facilitate. So what are the key things a facilitator will want to know, when they're trying to understand the system, before the big day itself?

Start with the ends

Your facilitator will always begin with the purpose or objectives - why is the meeting being held? What do you want to be different, after the meeting? This could be a difference in the information that people have (content), new agreements or decisions (process), or it could be that what is needed is a shift in the way people see each other (relationships) - or some of each of these things.

Context and history

Once the facilitator is confident that you are clear about the purpose (and this could take some time - the facilitator should persist!), then the facilitator will want to understand the context, and the people.

Context includes the internal context - what has you organisation done up to now, what other processes or history have led up to this workshop? It also includes the external context - what in the outside world is going to have an impact on the people in the room and the topic they are working on?

Who's coming?

Often, the one thing that has been fixed before the facilitator gets a look in is the people who have been invited. But are they the right people to achieve the objectives? Have some important oilers or spoilers, information holders or information needers been left out? And do they understand clearly what the objectives of the meeting are?

Getting the right people in the room (and making arrangements to involve people who need to take part, but can't actually be there on the day) is just part of it. What do the people need to know, in order to play an effective part in the meeting? And how far ahead does this information need to be circulated? Apart from passively receiving information, what information, views or suggestions can be gathered from participants before the meeting, to get people thinking in advance and save time for interaction and creative discussion on the day? What questions can be gathered (and answered) in advance?

What do the participants want out of the meeting? If this is very different to what the client or sponsor wants, then this gap of expectations needs to be positively managed.

When and where?

Apart from the invitation list, the other things which are usually fixed before the facilitator is brought in, and which they may challenge, with justification, are the date and the venue.

The date needs to be far enough away to ensure that participants get adequate notice, and the facilitator, client team and participants get adequate preparation time.

The venue needs to be suitable for the event - and for a facilitated meeting, traditional conference venues may not be. Inflexible room layout, a ban on blu-tack, rigid refreshment times - all of these make a venue hard to use, however handy it may be for the golf course. There's more on venues here.

Workshop design

Sometimes, of course, the date, venue and participant list are unchangeable, whatever the facilitator would like, and have to be taken as fixed points to be designed around. So what about the overall meeting design? The facilitator will want to understand any 'inputs' to the meeting, and where they have come from. They'll want to talk about the kind of atmosphere which will be most helpful, and about any fixed points in the agenda (like a speech by the Chief Exec), and how these can be used most positively.

A design for the meeting will be produced, and circulated to key people (the client, maybe a selection of participants), and amended in light of their comments. But the facilitator will always want to retain some flexibility, to respond to what happens 'in the room'.

What next?

And after the meeting? The 'after' should be well planned too - what kind of report or record is needed, and will there be different reports for different groups of people? This will have an impact on the way the meeting is recorded as it goes along - e.g. on flip chart paper, on display for all to see and for people to correct at the time. If there are specific 'products' from the meeting (agreements, action points, priorities, principles or statements of some kind, options or proposals), what is going to happen to them next?

And how will the client, facilitator and participants give and receive feedback about how the process worked?

All these things will need to be thought about early on - clients should expect their facilitators to ask about them all - and to help them work out the answers!

Challenging conversations

So to sum up, the facilitator will potentially challenge the client team about:

• Objectives • Context • Participants • Space • On-the-day process • Follow-up process

Free download

If you'd like to download a version of this, click here.

Leadership teams for collaboration

"Who will make sure it doesn't fall over?"

This was a question posed by someone in a workshop I facilitated, which brought together stakeholders (potential collaborators) who shared an interest in a water catchment.

It was a good question. In a collaboration, where equality between organisations is a value - and the pragmatic as well as philosophical truth is that everyone is only involved because they choose to be - what constitutes leadership? How do you avoid no-one taking responsibility because everyone is sharing responsibility?

If the collaboration stops moving forwards, like a bicycle it will be in danger of falling over. Who will step forward to right it again, give it a push and help it regain momentum?

Luxurious reading time

I've been doing some reading, in preparating for writing a slim volume on collaboration for the lovely people over at DōSustainability. (Update: published July 2013.) It's been rather lovely to browse the internet, following my nose from reference to reference. I found some great academic papers, including "Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice" by Chris Ansell and Alison Gash. This paper is based on a review of 137 case studies, and draws out what the authors call 'critical variables' which influence the success of attempts at collaborative governance.

It's worth just pausing to notice that this paper focuses on 'collaborative governance', which you could characterise as when stakeholders come together to make decisions about what some other organisation is going to do (e.g. agree a management plan for a nature reserve ), to contrast it with other kinds of collaboration where the stakeholders who choose to collaborate are making decisions about what they themselves will do, to further the common or complementary aims of the collaboration (e.g. the emerging work of Tasting the Future).

Leadership as a critical variable

Ansell and Gash identify leadership as one of these critical variables. They say:

"Although 'unassisted' negotiations are sometimes possible, the literature overwhelmingly finds that facilitative leadership is important for bringing stakeholders together and getting them to engage each other in a collaborative spirit."

What kind of person can provide this facilitative leadership? Do they have to be disinterested, in the manner of an agenda-neutral facilitator? Or do they have to be a figure with credibility and power within the system, to provide a sense of agency to the collaboration?

Interestingly, Ansell and Gash think both are needed, depending on whether power is distributed relatively equally or relatively unequally among the potential collaborators. It's worth quoting at some length here:

"Where conflict is high and trust is low, but power distribution is relatively equal and stakeholders have an incentive to participate, then collaborative governance can successfully proceed by relying on the services of an honest broker that the respective stakeholders accept and trust."

This honest broker will pay attention to process and remain 'above the fray' - a facilitator or mediator.

"Where power distribution is more asymmetric or incentives to participate are weak or asymmetric, then collaborative governance is more likely to succeed if there is a strong "organic" leader who commands the respect and trust of the various stakeholders at the outset of the process."

An organic leader emerges from among the stakeholders, and my reading of the paper suggests that their strength may come from the power and credibility of their organisation as well as personal qualities like technical knowledge, charisma and so on.

While you can buy in a neutral facilitator (if you have the resource to do so), you cannot invent a trusted, powerful 'organic' leader if they are not already in the system. Ansell and Gash note "an implication of this contingency is that the possibility for effective collaboration may be seriously constrained by a lack of leadership."

Policy framework for collaboration

I'm also interested in this right now, because of my involvement in the piloting of the Catchment Based Approach. I have been supporting people both as a facilitator (honest broker) and by building the capacity of staff at the Environment Agency to work collaboratively and 'host' or 'lead' collaborative work in some of the pilot catchments. The former role has been mainly with Dialogue by Design, and latter with InterAct Networks.

One of the things that has been explored in these pilots, is what the differences are when the collaboration is hosted by the Environment Agency, and when it is hosted by another organisation, as in for example Your Tidal Thames or the Brent Catchment Partnership.

There was a well-attended conference on February 14th, where preliminary results were shared and Defra officials talked about what may happen next. The policy framework which Defra is due to set out in the Spring of 2013 will have important implications for where the facilitative leadership comes from.

One of the phrases used in Defra's presentation was 'independent host' and another was 'facilitator'. It's not yet clear what Defra might mean by these two phrases. I immediately wondered: independent of what, or of whom? Might this point towards the more agenda-neutral facilitator, the honest broker? If so, how will this be resourced?

I am thoughtful about whether these catchments might have the characteristics where the Ansell and Gash's honest broker will succeed, or whether they have characteristics which indicate an organic leader is needed. Perhaps both would be useful, working together in a leadership team.

Those designing the policy framework could do worse than read this paper.

Do-ing it together

Have you come across Dō - new e-publishers who are bringing out a series of 90 minute reads on key sustainability topics? I particularly liked Anne Augustine's First 100 Days on the Job, for new sustainability leads. Now I've been asked to write a slim volume on collaboration for the great people at Dō. I'm very excited about this - and I want to do it collaboratively.

So tell me: what are your favourite examples of successful sustainability collaborations?

Collaboration: doing together what you can't do alone; doing together what you both/all want to do; sharing the decision-making about what you do and how you do it.

Post a comment here, or email me.

Thanks, collaborators!

Occupy movement: the revolution will need marker pens

On my bike, between meetings last week, I was passing St Paul's Cathedral in London so I wandered through the Occupy London Stock Exchange 'tent city'. Occupy LSX has divided opinion. At the meeting I was going to - a workshop of organisational development consultants, facilitators, coaches - some people made rather snide remarks about the likely impact of the first cold weather on the protesters, and about unoccupied tents. There's a retort here about the infamous thermal imaging scoop. Others were interested in and sympathetic to the dissatisfaction being expressed, but frustrated by the lack of a clear 'ask' or alternative from the occupiers.

Emergent, self-organising, asks and offers

What struck me, however, were the similarities between the occupy area itself, and some really good workshops I've experienced. There was plenty of space given aside for 'bike rack', 'grafitti wall' and other open ways of displaying messages, observations or questions. There was a timetable of sessions being offered in the Tent City University, and another board showing the times of consensus workshops and other process-related themes.

There was a 'wish list' board, where friendly passers-by could find out what the protesters need to help keep things going. Marker pens and other workshop-related paraphernalia are needed, as well as fire extinguishers and tinned sweetcorn.

I saw these as signs of an intentionally emergent phenomenon, with a different kind of economy running alongside the money economy. Others have blogged about the kinds of processes honed and commonly in use at this kind of event or camp, in particular if you're interested there's loads on the Rhizome blog.

Don't ask the question if you don't already know the answer?

I recognise the frustration expressed by some of my OD colleagues about the lack of clearly-expressed alternatives. This kind of conversation often occurs in groups that I facilitate: someone (often not in the room) has expressed a negative view about a policy, project or perspective. The people in the room feel defensive and attack the grumbler: "I bet they couldn't do any better" or "what do they expect us to do?". Some management styles and organisational cultures are fairly explicit that they don't want to hear about problems, only solutions. (Browsing here gives some glimpses of the gift and the shadow side of this approach.)

But I see something different here: a bottom-up process where people who share broadly the same intent and perspective, come together to explore and work out what they agree about, when looking at the problems with the current situation and the possible ways of making things better. The are participatively framing a view of the system as it is now, and what alternatives exist. This takes time, of course.

They are also, as far as I can tell from the outside, intentionally using consensus-based processes rather than conventional, top-down, leader-led or expert-led processes to organise this. Understandably frustrating for the news media which rely increasingly on short sound-bites and simple stories with two sides opposing each other. And it could get very interesting when the dialogue opens up to include those who have quite different perspectives on "what's really going on here" (for example mainstream economists, bankers, city workers).

The other thing I notice about this expectation of a ready-made coherent answer, is how similar it is to some group behaviour and the interventions made by inexperienced facilitators and coaches. When I am training facilitators, we look at when to intervene in a group's conversation, particularly when to use the intervention 'say what you see'. (This makes it sound very mechanical - of course it's not really like that!)

The trainee facilitator is observed practising, and then there is feedback and a debriefing conversation. Perhaps they chose not to intervene by telling the group what they observed. Sometimes during this feedback and debrief, a trainee will say something like "Yes, I noticed that, but I didn't want to say anything because I wasn't sure what to do about it or what it meant." They are assuming that you can only 'say what you see' if you know what it means and already have a suggestion about what to do about it.

But it also serves a group to say what you see, when you haven't a settled interpretation or clear proposal. (In fact, it is more powerful to allow the group to interpret, explain and propose together.) All questions are legitimate, especially those to which we don't (yet) know the answer. Ask them. Guess some answers. And this - for the time being - is what the occupy movement is doing.

The revolution will need marker pens

All this consensus-based work and open-space style process needs plenty of marker pens (permanent and white-board). So if you have a bulging facilitation toolkit and you're passing St Paul's, you know what to do!

Update

Others have spotted these connections too. Listen to Peggy Holman talking about Occupy Wall Street on WGRNRadio, 9th January.